The Seas Are Rising—And So Are They

Outside the United Nations building in New York City, a murmur echoed through the security line posted alongside First Avenue as Al Gore was escorted into a cordoned-off area. It was September 23, the temperature approaching a humid 90 degrees on the first day of fall, and the U.N. Climate Action Summit was set to begin, paving the way for December’s Climate Change Conference, COP25, in Santiago, Chile. António Guterres, the United Nations secretary-general, had invited world leaders with an admonition: “Don’t come to the summit with beautiful speeches,” he said, but with “concrete plans—clear steps to enhance nationally determined contributions by 2020—and strategies for carbon neutrality by 2050.”

Perhaps predictably, the story of the summit was ultimately not the solutions offered, but the urgent need for them. Three days earlier, approximately 4 million people in 185 countries had participated in coordinated global climate change strikes as part of the youth-led Fridays for Future movement begun by 16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. Gore, whose 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth cast global warming as a “planetary emergency,” spoke to the cameras. “They’re here, basically, to shame the adults,” I heard him say.

A moment later, another, more visceral murmur rippled through the security line as Thunberg walked swiftly past, her shirt a magenta blur, her braid swinging down her back, to deliver a call to action stinging with righteous anger.

“We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth,” she said. “How dare you?” Her speech lasted approximately four and a half minutes. Thunberg did not waste any time—the point being, of course, that there is no time to be wasted.

After her speech, Thunberg joined 15 other activists from around the world at UNICEF to collectively launch a formal legal complaint against Brazil, France, Germany, Argentina, and Turkey alleging that the countries are violating their rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child by failing to sufficiently address climate change. Three of the petitioners are from the Marshall Islands, which are at risk of becoming uninhabitable as soon as 2030. The youngest of the named petitioners is eight.

Joshua Harkness, Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Jeffrey Atias, Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

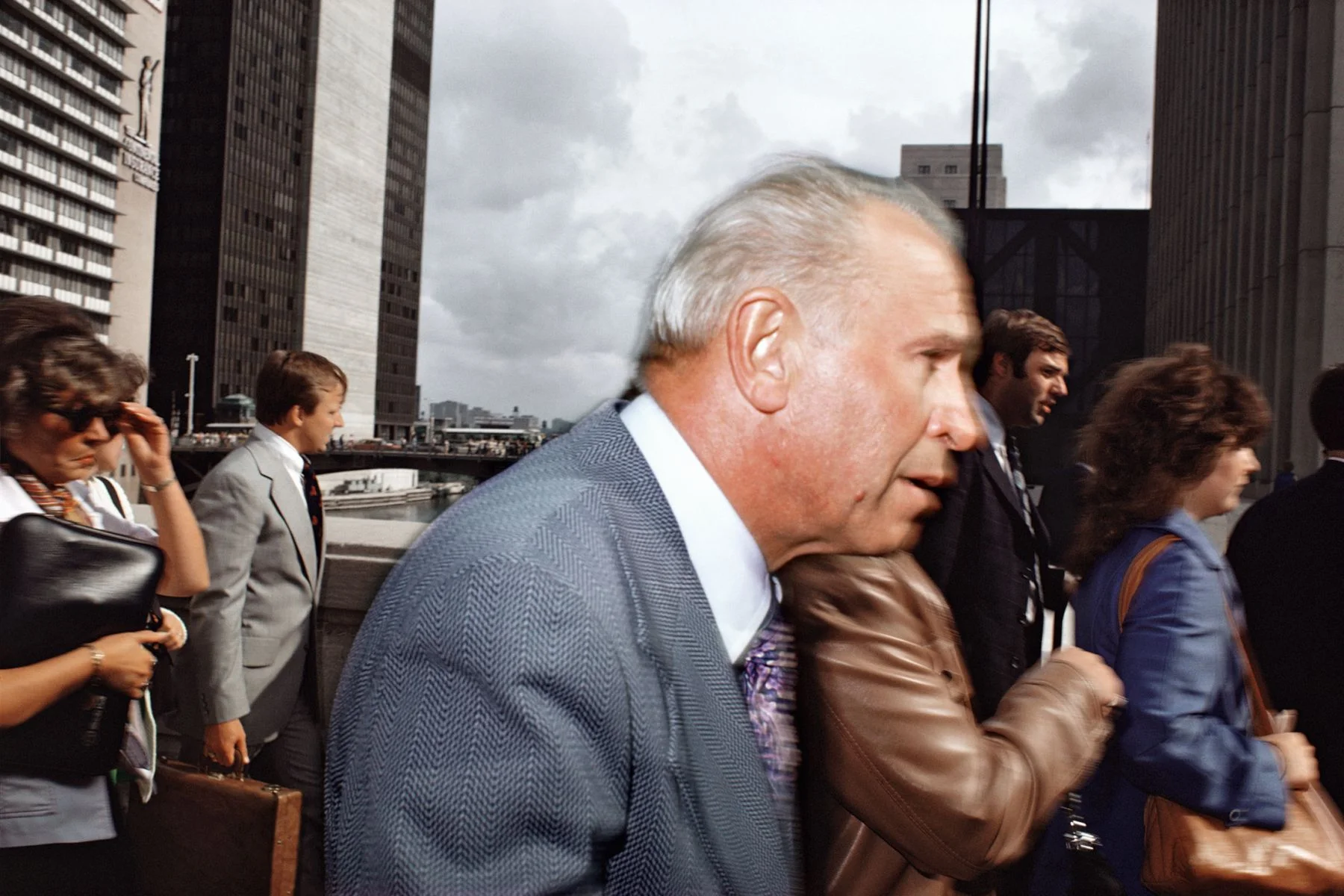

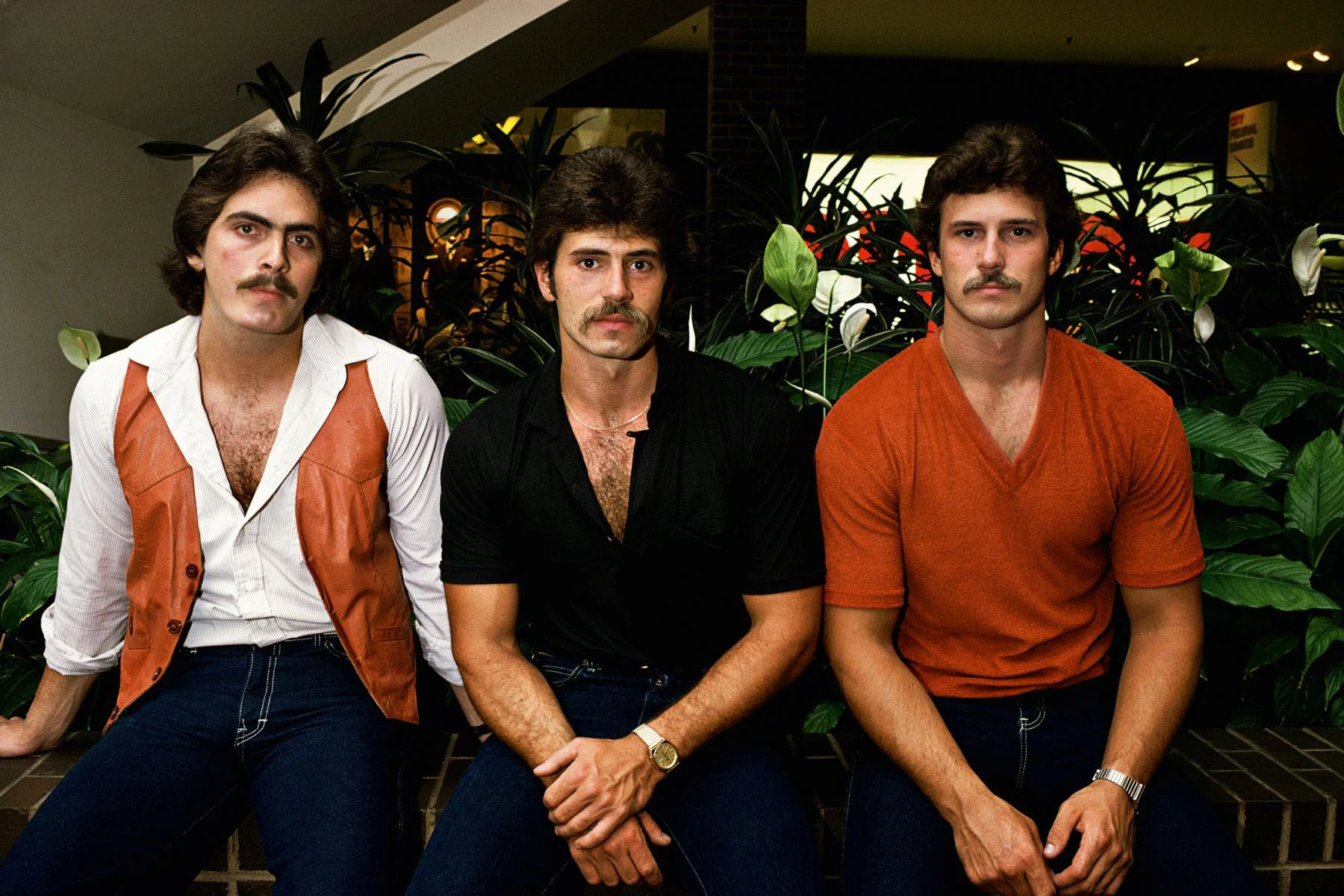

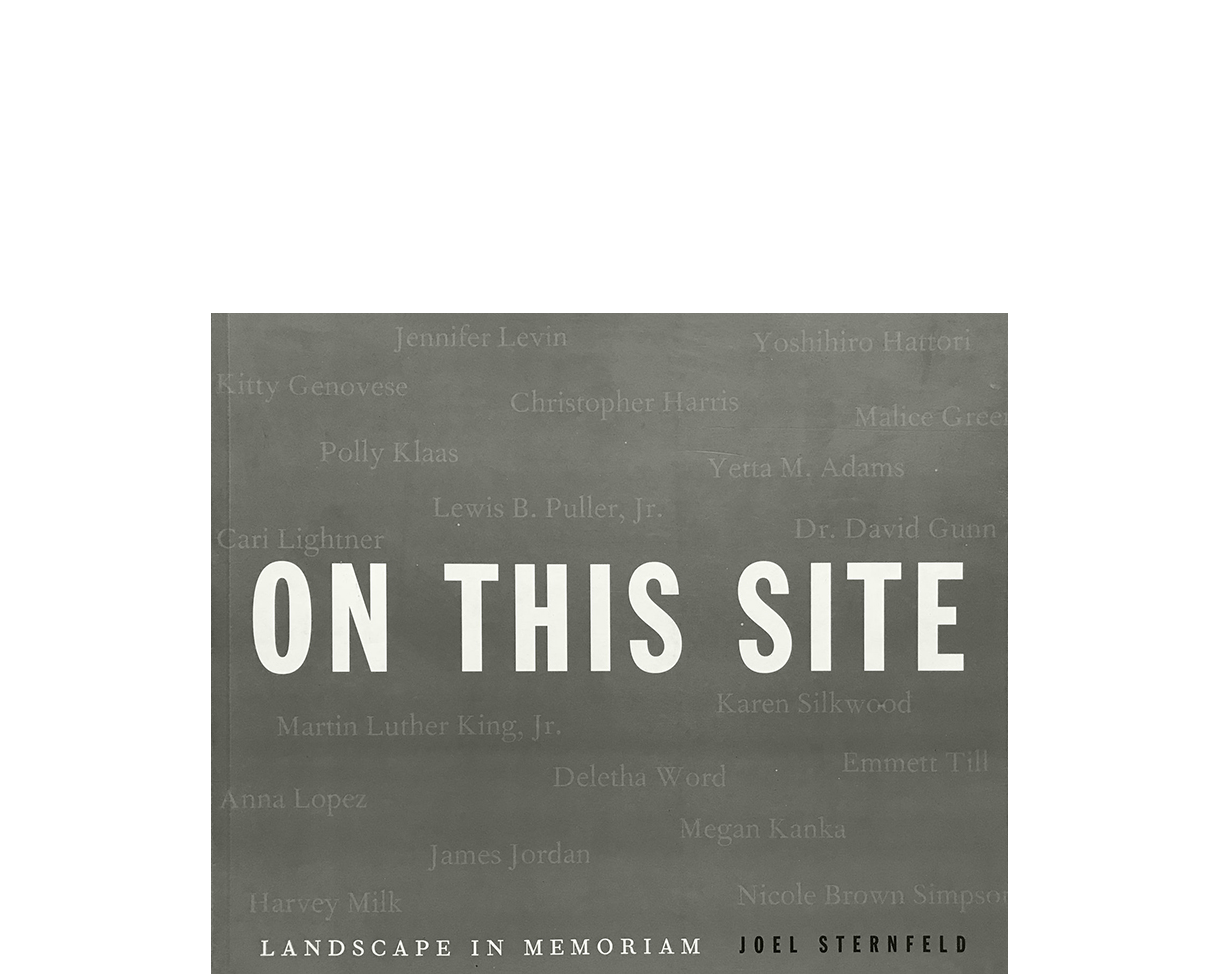

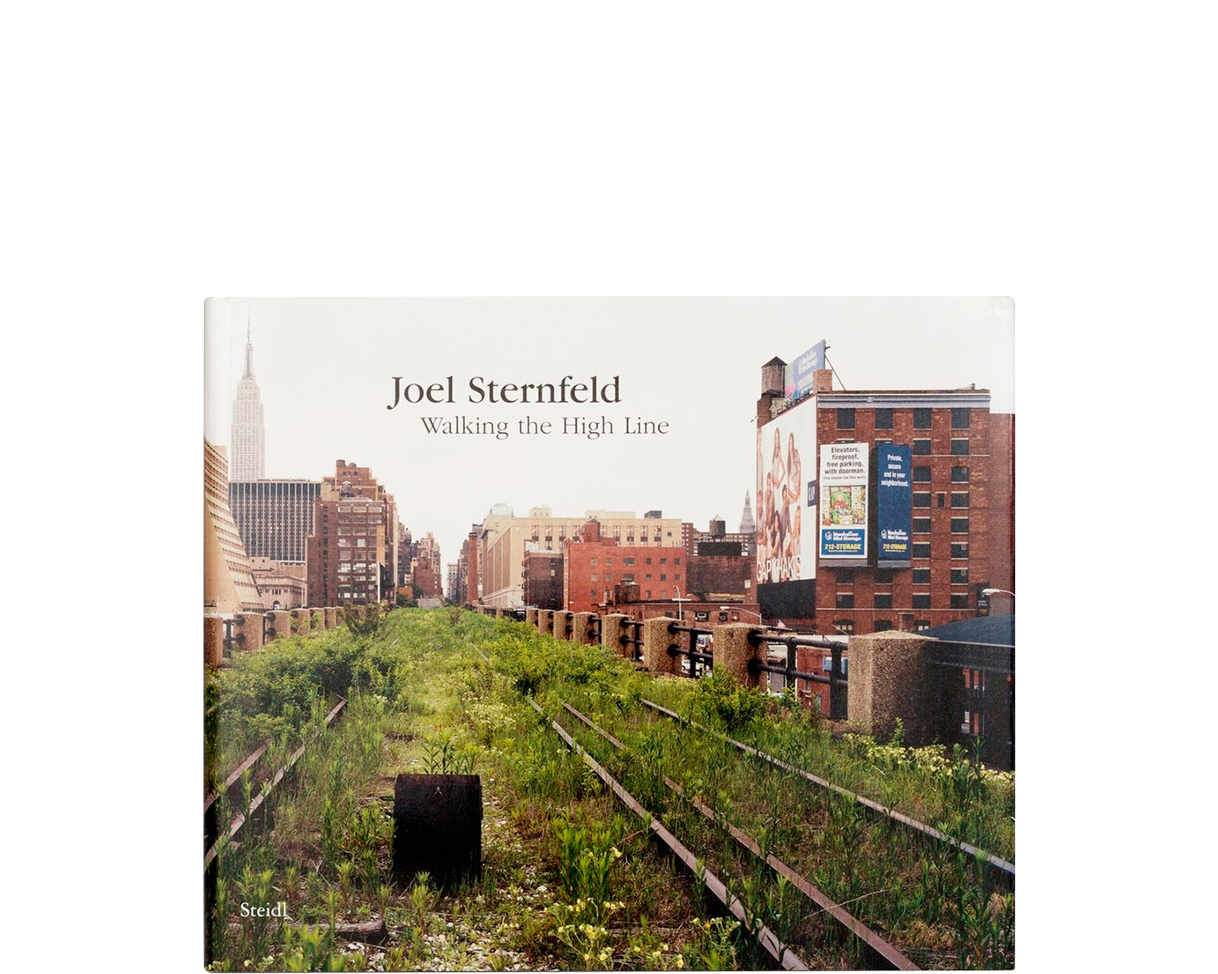

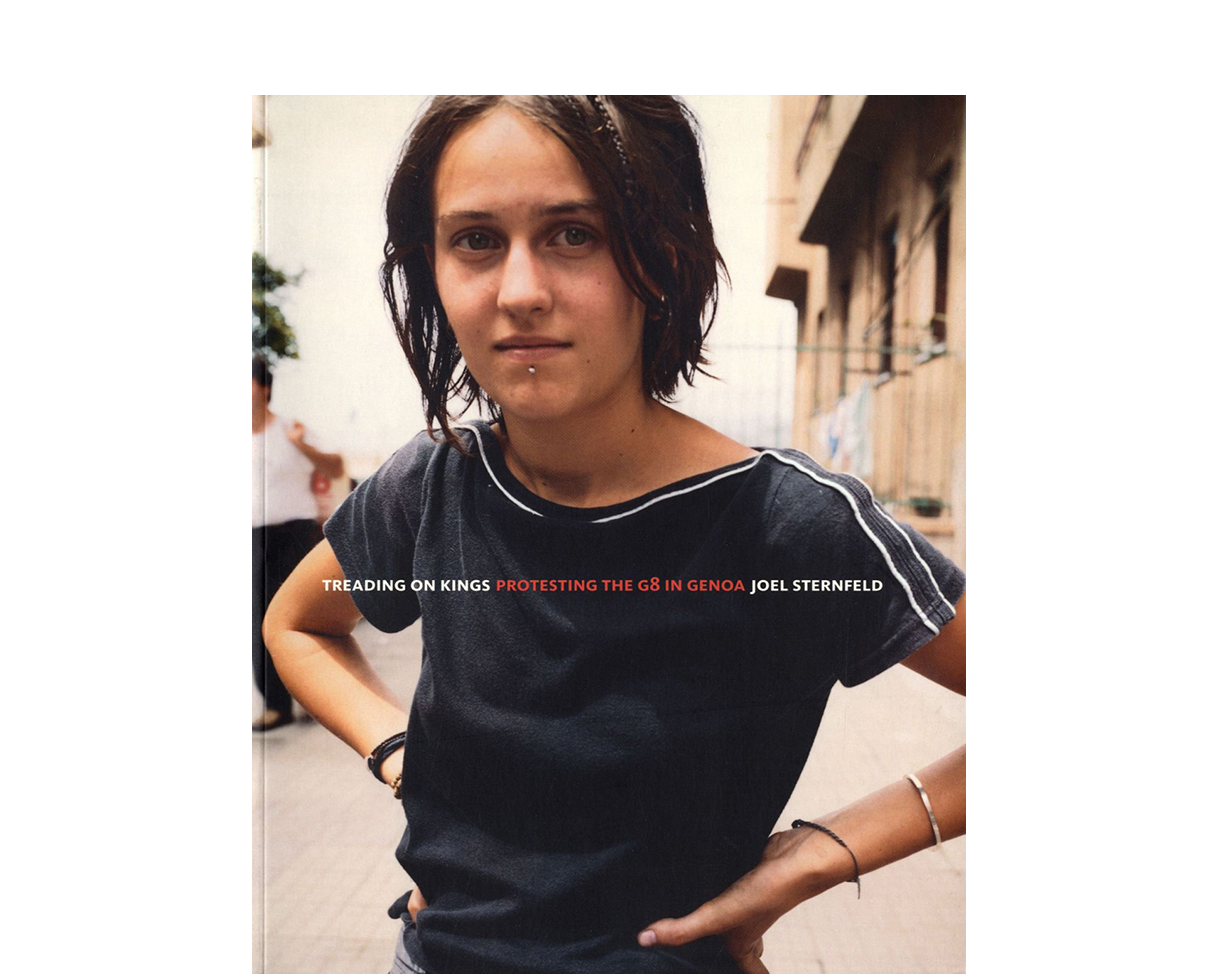

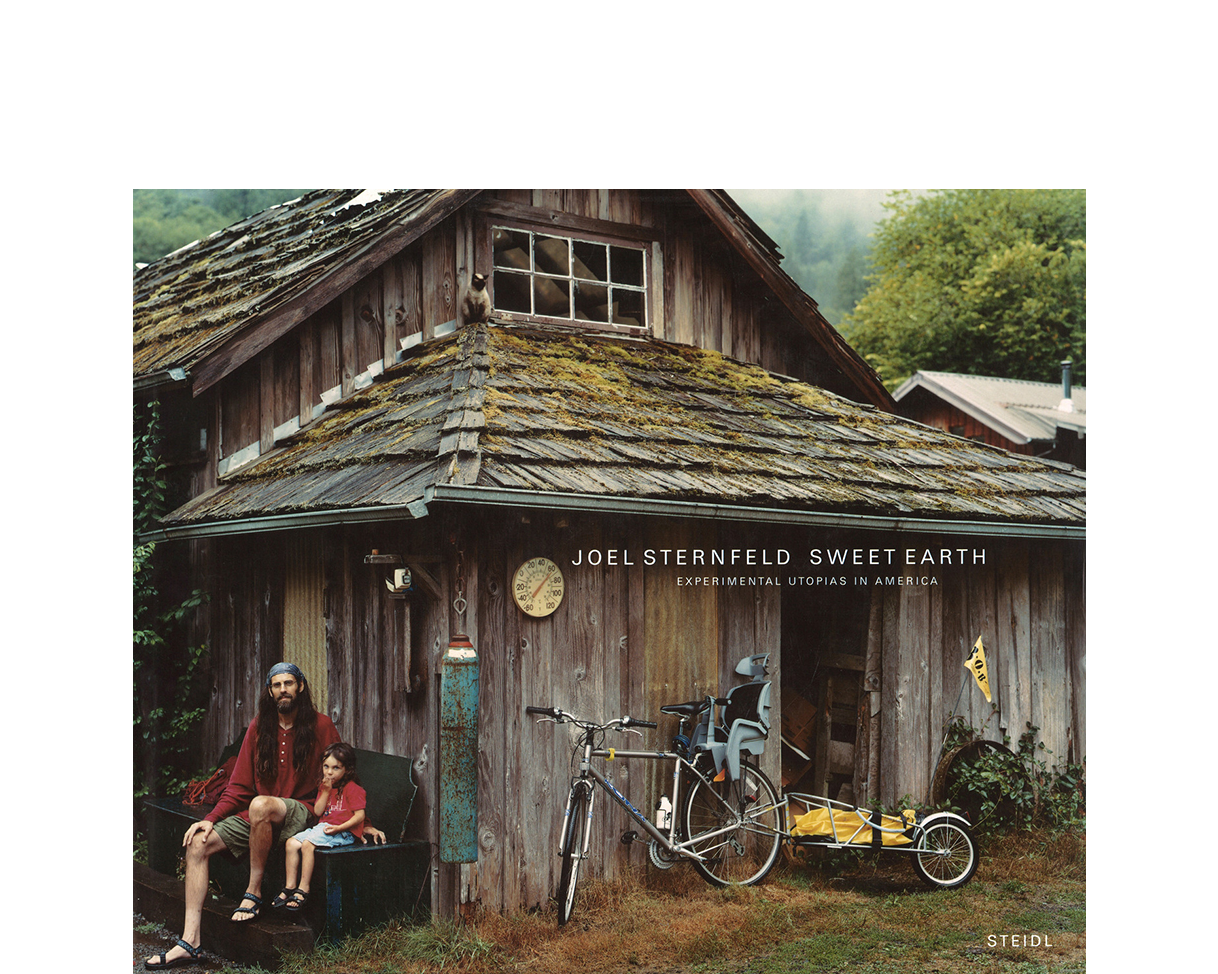

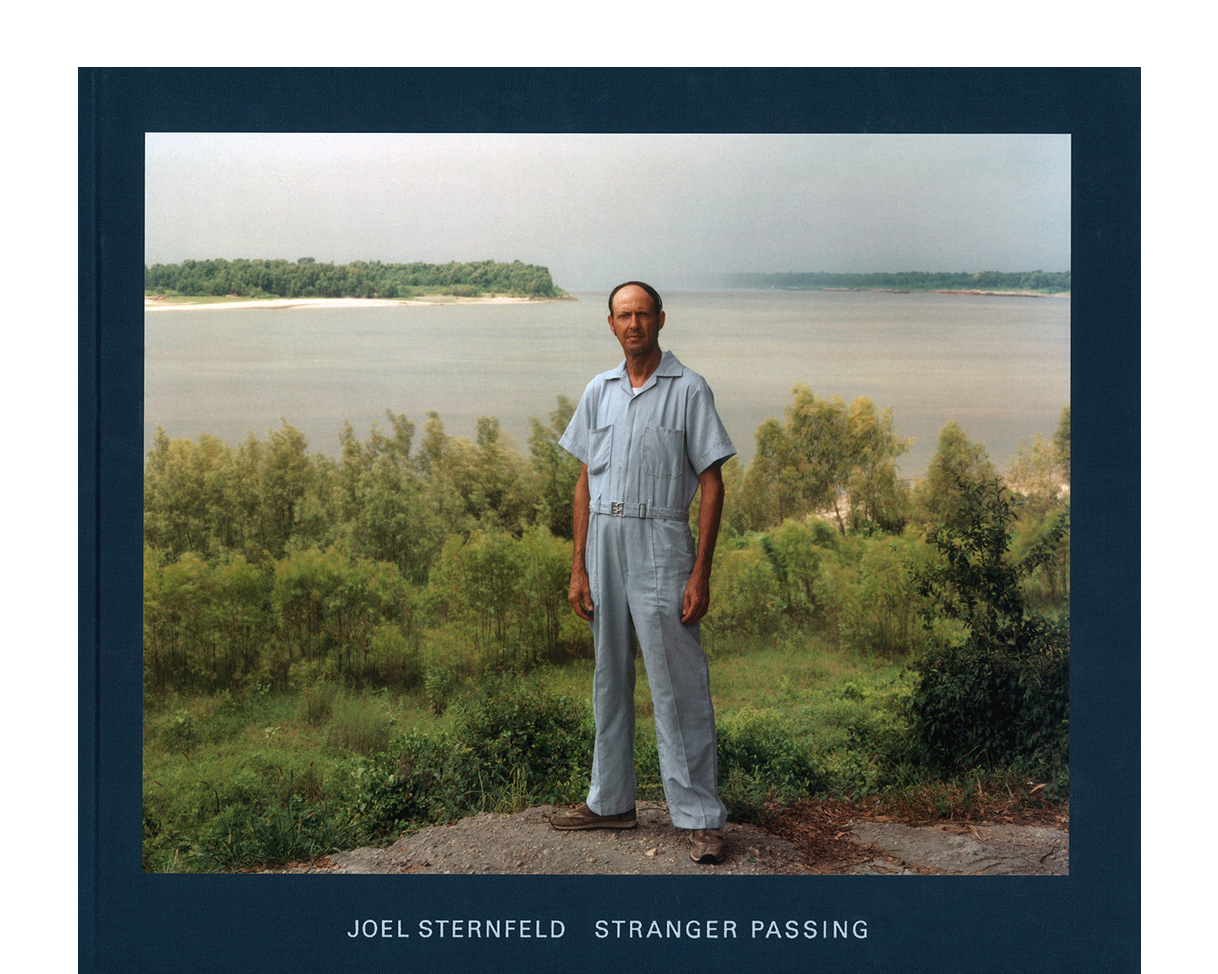

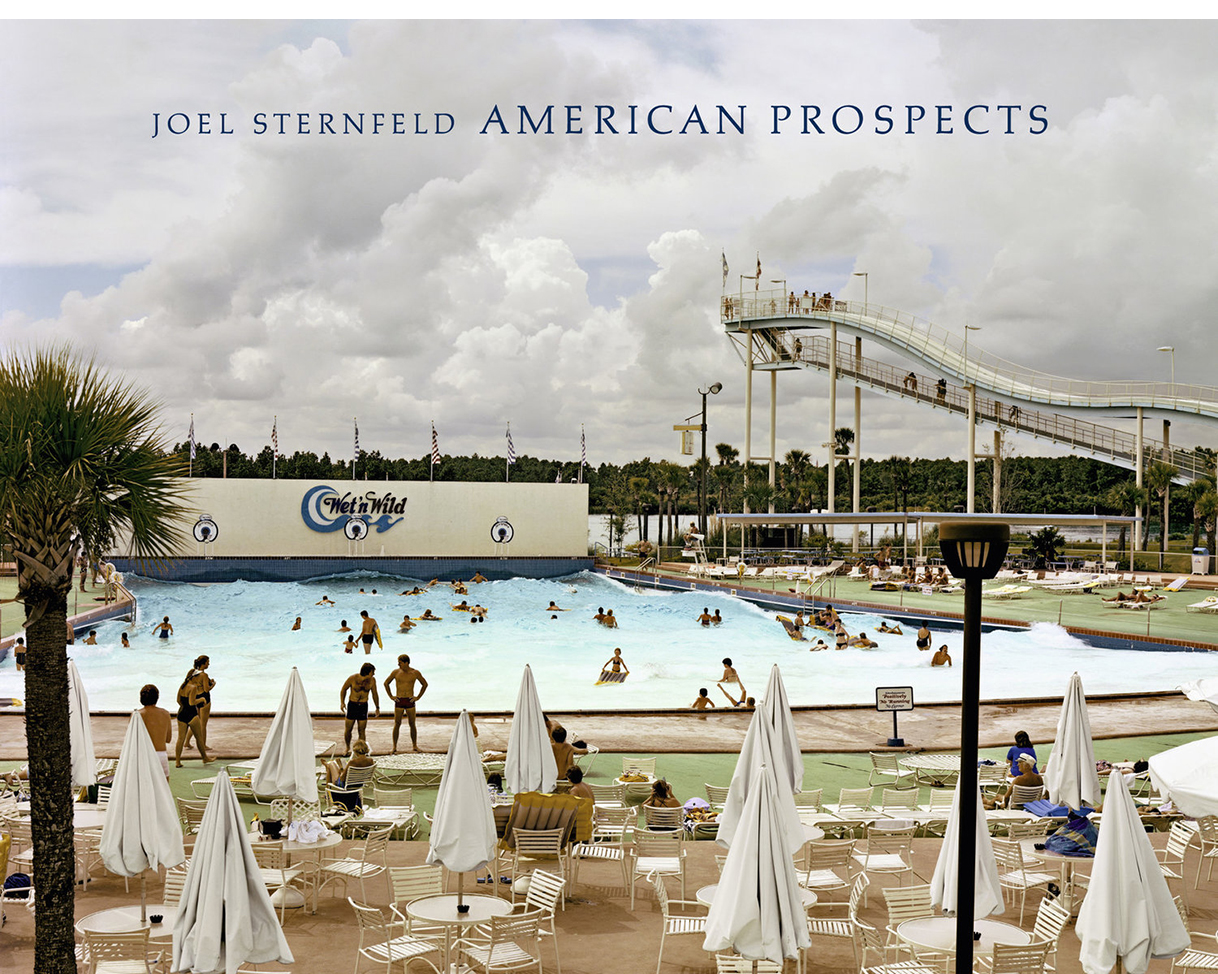

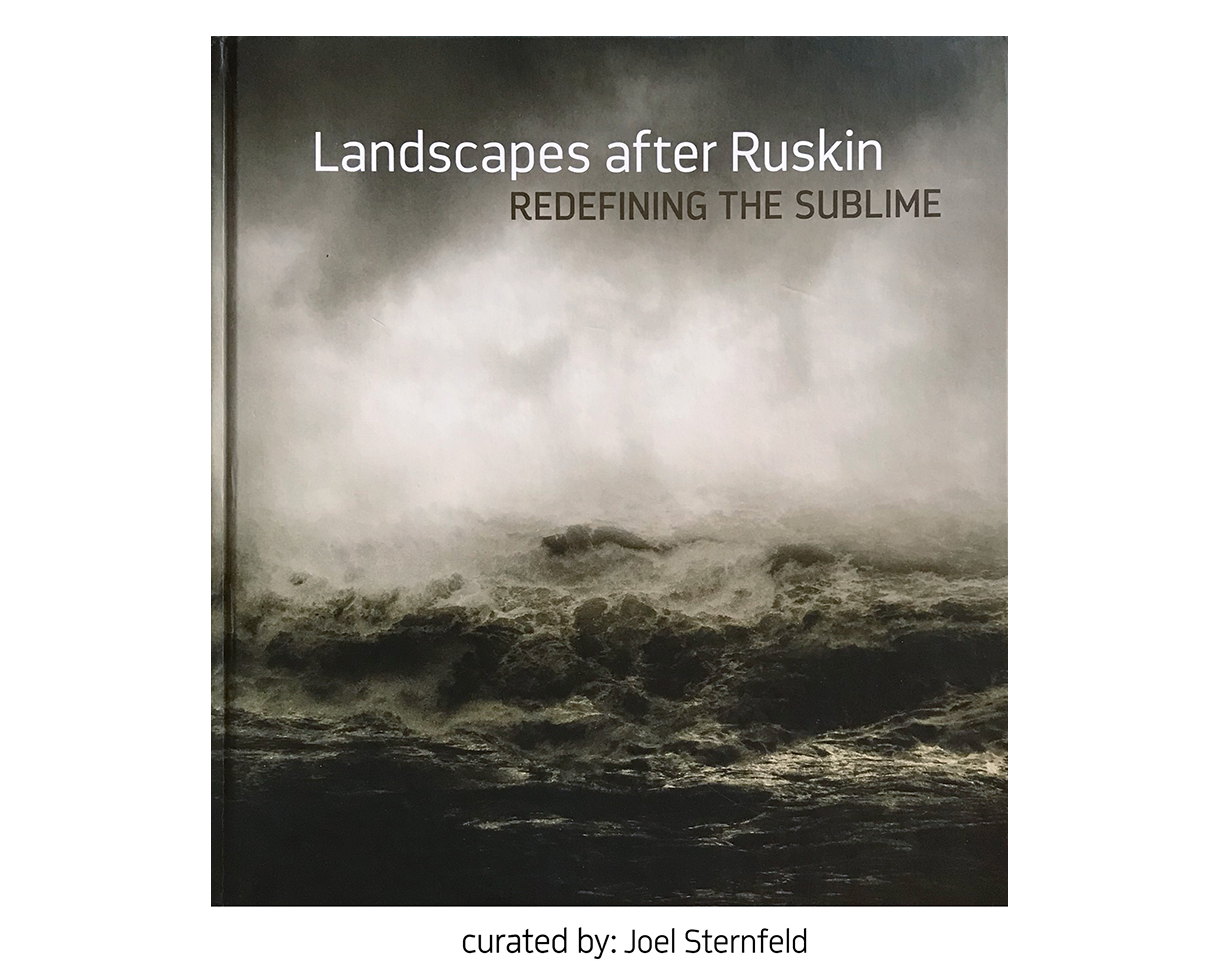

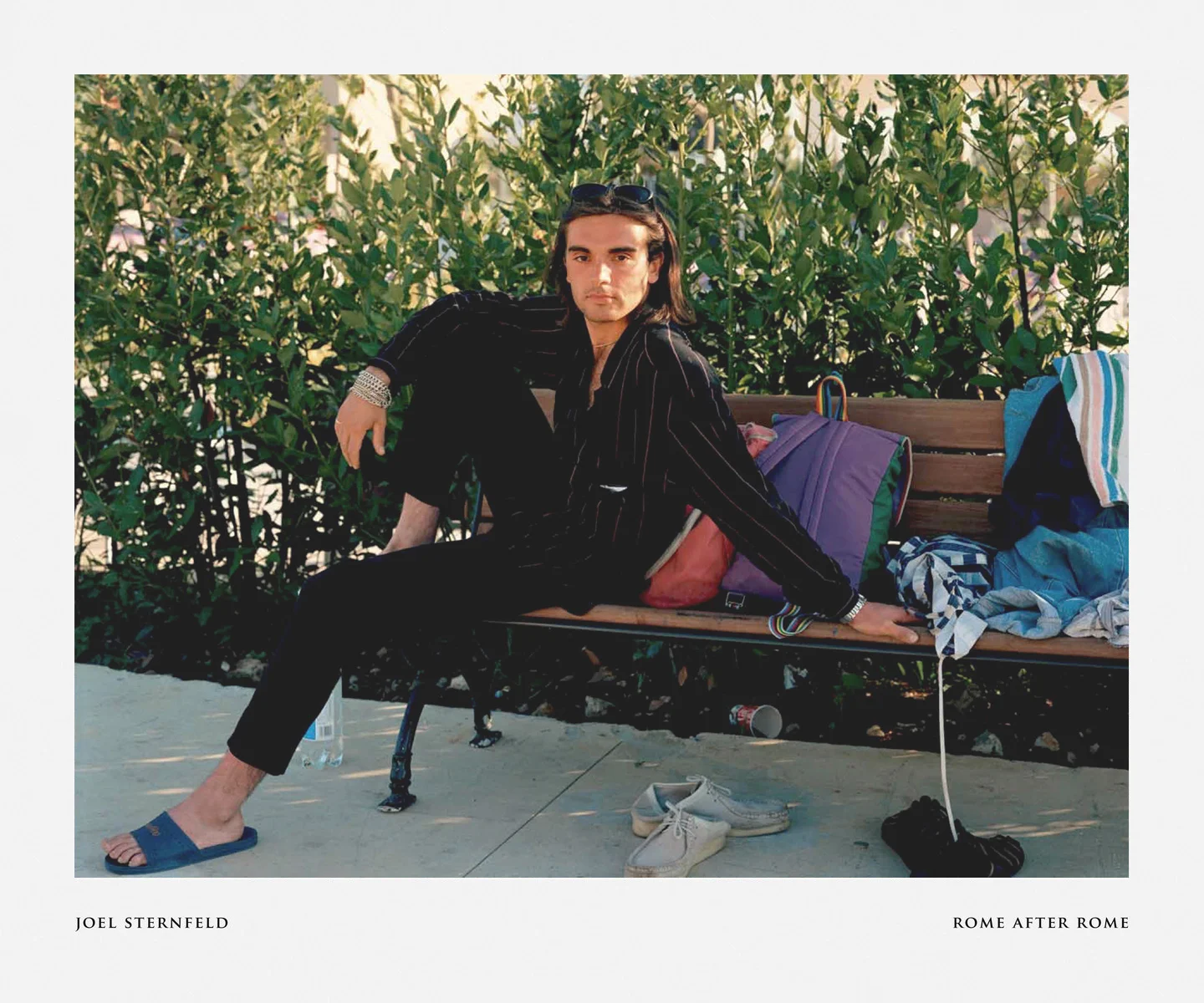

Many of them were not yet born when the photographer Joel Sternfeld, whose pictures accompany this story, attended the 2005 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Montreal. He photographed the leaders coming to terms with global warming for his 2008 book When It Changed. This week, he had returned to make portraits of young people calling out some of those same leaders for failing to implement any real plan over years of inaction and denial spanning their entire lifetimes.

Diana Viglucci, Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Sophie Mohammed, Climate Strike, Battery Park, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

By the end of the day, 65 countries (now up to 77) had announced efforts to become carbon-neutral by 2050; the president of the United States, the world’s second worst polluter, had managed to stop by the assembly for less than 15 minutes—15 minutes longer than anyone expected—and yet none of it was nearly enough. As Thunberg said, the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global temperature increase to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and which President Trump has threatened to exit, is insufficient: “There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable, and you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.”

Anaya Robinson, Climate Strike, Foley Square, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Her own numbers—which would reach 7.6 million participating in youth-led climate strikes around the world during the week—echoed resoundingly. Though few of them ever made it past the U.N. security lines, the streets were theirs. The seas are rising, they chanted, and so are we.

Priyadharshany Sandanapitchai, Climate Strike, Foley Square, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Maria Psomas, Climate Strike, Foley Square, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Nalyejah Meyers, Climate Strike, Foley Square, New York City, September 20, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Throughout Climate Week, youth-led actions reverberated within and outside the U.N. After organizing and leading a climate strike in Milwaukee on Friday, 17-year-old Ayanna Lee traveled to New York for the U.N. youth summit that weekend. She arrived at the U.N. with a symbolic green streak in her hair. “It felt good to be around people who are doing the work we are also doing and to talk about it,” she said. “But I shouldn’t have to be here. It’s really frustrating that I’m having to meet with people 20 years older than me who should be doing their job without having a high school senior tell them how to do it.”

On Monday, as Thunberg made her address, the industry-led Oil and Gas Climate Initiative meetings were under way inside the Morgan Library. Outside, activists from 350.org, the watchdog group Corporate Accountability, and the youth-led SustainUS unfurled a banner that wrapped around 37th Street and Madison Avenue, painted with the words “Exxon knew, make them pay.”

Two of the banner holders, Lena Greenberg, 23, and Swetha Saseedhar, 24, both of SustainUS, had managed to briefly infiltrate an Oil and Gas Climate Initiative reception the night before in an action that would have done the Yes Men proud. They and five others dressed as waiters and attendees—the “waiters” wore black pants, white shirts, and aprons; the “attendees” dressed in black-tie attire—and attempted to enter the dining room. “We were going to present them with this,” said Greenberg, holding up a plaque they’d concealed beneath a serving tray prop. It read, “We Knew: In recognition of our years of climate change denial, false solutions, inaction, and the horrifying harms we’ve inflicted on the people and the planet.”

“The security guards were pretty amused,” Greenberg said, but the two of them were swiftly escorted out by eight members of security and NYPD. Saseedhar, who lives in New York, said family members in Chennai, India, hadn’t had access to clean water in months. If she had been allowed inside the conference, she said, she would have demanded the oil executives pay climate reparations to communities destroyed by the effects of fossil fuel extraction and global warming.

Ayanna Lee, Cofounder of Youth Climate Action Team of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Wisconsin), at the Youth Climate Summit, the United Nations, New York City, September 21, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Greenberg agreed. “I have deep respect for the work Greta has done and the number of people she’s mobilized, but it’s also really helpful for the fossil fuel industry to have this narrative that young people want a future,” they said. “It lets them off the hook for paying for their historic responsibility. Young people, let it be known, are not just demanding a future—we are demanding a livable present for the whole world.”

Eshaan Menon, Winner of the Reboot the Earth Hackathon in Malaysia, Youth Climate Summit, the United Nations, New York City, September 21, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

On Wednesday evening, the taxidermied polar bear that awaits visitors at the Explorers Club on East 70th Street was more disconcerting than usual as guests trailed in to a panel about the results of the IPCC special report, released that morning, on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. The third in a trilogy of the U.N. intergovernmental panel’s studies, authored by 100 scientists worldwide, it found that sea levels are rising faster than predicted—which issues a direct challenge to leaders meeting at COP25 in December. If current carbon emissions continue unabated, the report predicts a catastrophic reordering of life: depleted fisheries, widespread illness, a severe rise in extreme weather events and massive coastal flooding, the loss of homeland for residents of island nations, melting glaciers, and mass extinction.

Elena Nalato, Youth Climate Summit, the United Nations, September 21, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Eleala Avantale, Tuvalu Red Cross Society, Youth Climate Summit, the United Nations, New York City, September 21, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Edward Shadwig, Micronesian Red Cross Society, Youth Climate Summit, the United Nations, September 21, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

“The sea ice in the Arctic has disappeared by 75 percent in only 40 years,” Jennifer Francis, a scientist who studies the effects of rapid Arctic warming on extreme weather patterns, told me. Like many of her peers in the room, she had seen the report just hours earlier. The news it offered was not new, but it put the climate emergency in stunning perspective: “It’s the magnitude of that kind of change that is so breathtaking.” Before she joined the Woods Hole Research Center, Francis taught at Rutgers University for 24 years, watching her students grow increasingly galvanized. “Most of them have lived their entire lives on a dramatically heating planet,” she said. “They’re up in arms.”

I had come to the summit thinking that after the strikes, there might be a story in the world leaders’ responses, but few of them were as willing to grapple with the youth’s demands as Iceland’s prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir. Jakobsdóttir opened the event by praising the youth leading the charge, and added her own plea to theirs. “The stakes could not be higher,” she said. One month earlier, Jakobsdóttir had made headlines when she held a funeral for Okjökull, the first glacier lost to the effects of human-inflicted climate change. By 2200, all of Iceland’s glaciers could be gone. “When you stand on a glacier, you can actually hear it,” Jakobsdóttir told the room, which went quiet. “I don’t know the word for it in English, but you can really hear the sound of it retreating.”

It was a sobering moment, even for a room full of scientists. I thought back to something 14-year-old Fijian activist Timoci Naulusala had told me three days earlier. Sitting in a studio in the UNICEF building after the global summit, Naulusala, who at 12 gave a stirring speech at COP23 in Bonn after his village was destroyed by a cyclone in 2016, had gently but firmly corrected me: “There is not much time, but there is still time.”

Timoci Naulusala of Fiji, who first spoke to world leaders at COP23 in Bonn, Germany in 2017, at the UNICEF Headquarters in New York City on September 23, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Alexandria Villaseñor, a high school student who began striking outside the United Nations as part of the Fridays for Future movement on December 14, 2018. She is seen at the UNICEF Headquarters in New York City on September 23, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

On September 27, as Greta Thunberg prepared to address more than 500,000 strikers in Montreal, it should have been back to the usual Fridays for Future protests for 16-year-old Alexandria Villaseñor in New York—except it wasn’t. The bench where Villaseñor has protested nearly every Friday outside the U.N. since December 14 had been cordoned off and surrounded by news cameras.

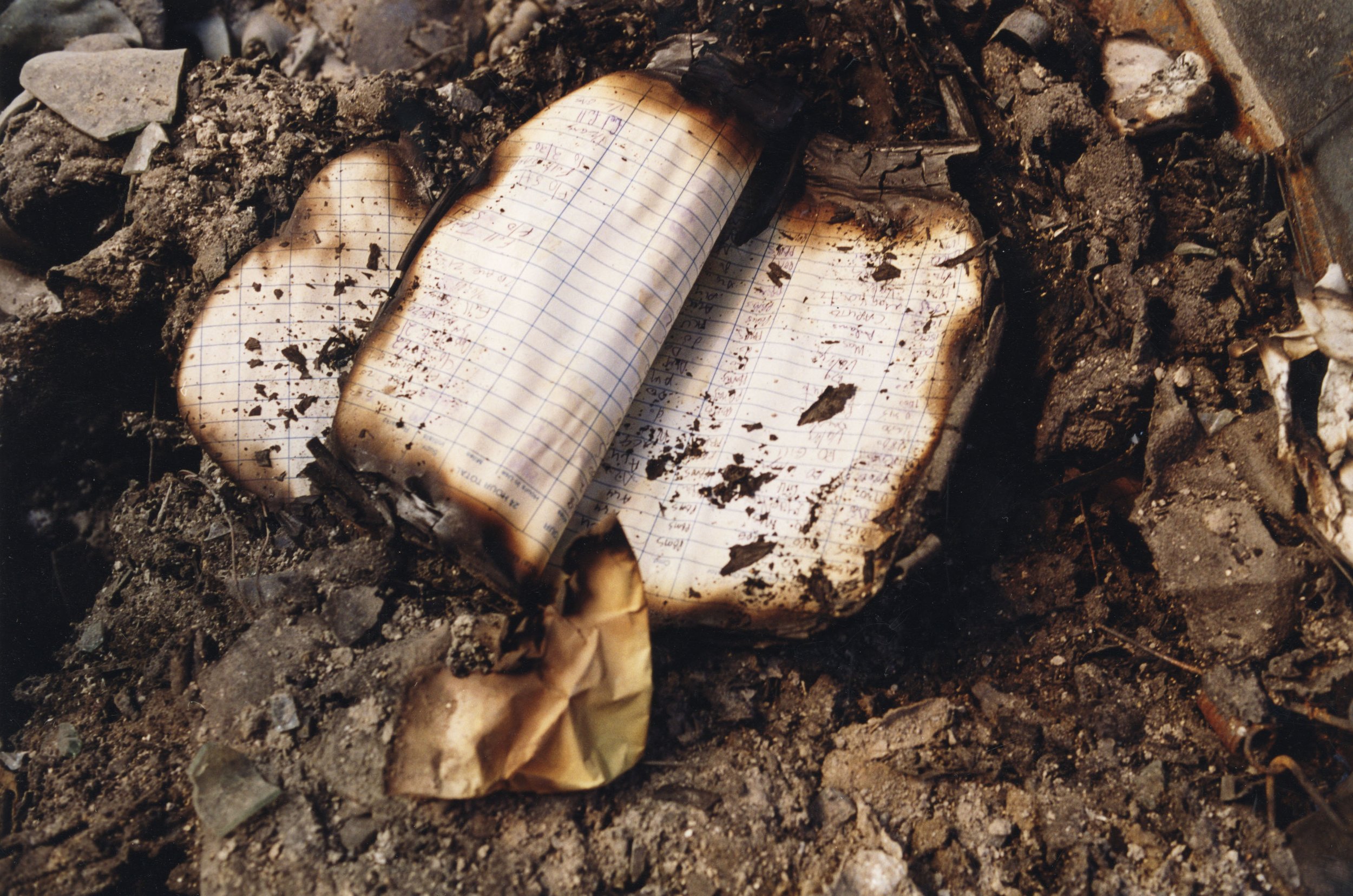

Last October, Villaseñor’s visit back home to northern California coincided with the Camp Fire that burned through the town of Paradise in minutes; the smoke that carried to Davis, where she was staying, badly exacerbated Villaseñor’s asthma. When she returned to New York, she was sick for weeks. Her mother, Kristin Hogue, a doctoral student, brought her daughter along to her graduate classes in climate science, not realizing how closely Villaseñor was paying attention; spurred on by Thunberg’s speech at COP24, she began to draw the connections between frequent, devastating wildfires and human-triggered climate change. “I didn’t even know what an activist was,” Villaseñor told me. “I just knew I had to do something.”

On this particular Friday, across from the U.N., Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza had been blocked off and transformed into a maze of protests from all over the world: cries of “Free Kashmir” mingling with Chinese phrases, a cacophony of voices fighting to rise over the din. Villaseñor, who cofounded the group Earth Uprising, was joined there by Maria Riker and Cleo van Haaften, 13-year-old students at the Institute of Collaborative Education who have been striking with her for eight months. “It does make us angrier at adults as time goes by and we’re still out here,” Riker said. “They’ve known about this for years and no one has done anything, and now it’s on our shoulders. But we’ll continue striking as long as we have to. We’ve got to save the world before it ends.”

Aaron Elavera Thomases (“Save Our Mother”), who has been striking since March 2019, at a Fridays for Future strike at City Hall, New York City, September 27, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

As the volume of nearby protests rose, Villaseñor looked longingly across the avenue at her captive bench. In keeping with her usual suffragette white, she wore a white Patagonia vest over her shirt and printed white pants. She carried her “School Strike 4 Climate” sign; at one point, she used it to swat away a bee that had landed on my back. Beatrice Fihn, director of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize–winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, showed up in a shirt stenciled with a disarmament symbol and faded jeans. She embraced Villaseñor warmly. “It’s always girls and women who are daring to do this work, isn’t it?” Fihn said to me.

In fact, many of these people have since become Villaseñor’s close friends, a network of fellow activists who organize on Slack and Instagram and iMessage. “Her job is much harder than mine,” Hogue had told me. That morning, Villaseñor, who is undertaking a year of independent study, had announced that when her mother returns to California, she’ll embark on a tour of her own, striking in a different city almost every Friday: “Wherever I go, my sign will be with me.”

Maria Riker, protesting at the United Nations, Dag Hammerskjöld Plaza, New York City, September 27, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Now it went with her downtown to City Hall, where a dedicated, forceful contingent of strikers raised signs, waved flags, and chanted on the sidewalk. Among them was Autumn Peltier, the chief water commissioner of the Anishinabek Nation, which includes 40 First Nations across Ontario, Canada, who was celebrating her 15th birthday. She was also preparing to give her second speech at the U.N. the next day: a plea for clean water. The audience, she told me days later from her home on Wikwemikong Unceded Territory in northern Ontario, felt different than in 2018. “I felt heard this time,” Peltier said. “I felt like I was being listened to.”

At 15, Peltier (who began her activism at eight, following in the footsteps of her great-aunt, the activist and founder of Mother Earth Water Walkers, Josephine Mandamin) was one of the older members of the day’s youth climate strike. It was the first strike ever for Gabriela Nunes, 10, and Trisha Iyer, 11. “I forced her to come,” Nunes told me. “You did not!” Iyer said. “I did,” Nunes insisted. “I tried to get, like, seven more people too, but no one could get their parents to let them.” They are both in sixth grade at Ardsley School in Westchester; Iyer wants to be a social scientist, a political scientist, or a cello player, and Nunes already has a side hustle as a budding chef. “Most of them don’t know what’s happening,” Iyer said of their fellow students. “They’re playing video games,” Nunes sighed.

Nunes, who had watched Thunberg’s U.N. speech “five or six times,” had been determined to come to the strike that day; her mother, Liz Bacelar, had tried to bribe her to go to school instead. But in the end, she relented and missed work to accompany both girls to the protest. “I had assumed this was all being started by activist parents,” Bacelar told me. “But when I got here, I saw all these moms who were just like me, led to strike by their children.”

Trisha Iyer (Left) and Gabriella Nunes after a Fridays for Future strike at City Hall, New York City, September 27, 2019.Photographed by Joel Sternfeld

Around 1:30 p.m., the strikers collectively sat down on the sidewalk and implored passersby, “Don’t just watch us—join us.” It was the close of a week during which they’d pulled off the biggest climate protest in history. Still, world leaders had again failed to offer a concrete plan, so the youth strikers continued ahead with their own. Afterward, some would join another protest, the Communities Strike for Climate Over Colonialism, in Brooklyn. Levi D., the youngest plaintiff named in the Juliana vs. U.S. climate lawsuit, would head back that day to his home on a barrier island in Florida. Villaseñor had a rehearsal for the Global Citizen Festival, where she would join fellow youth activists Xiye Bastida and Selina Neirok Leem onstage the next afternoon. Amanda Cabrera, who at eight had just finished her fifth climate strike, checked in with friends before leaving. “47th and First,” they said, referring to the location of Villaseñor’s bench outside the U.N. “See you next week.”