“The Incredible Commonplace.” New York Times by Andy Grundberg

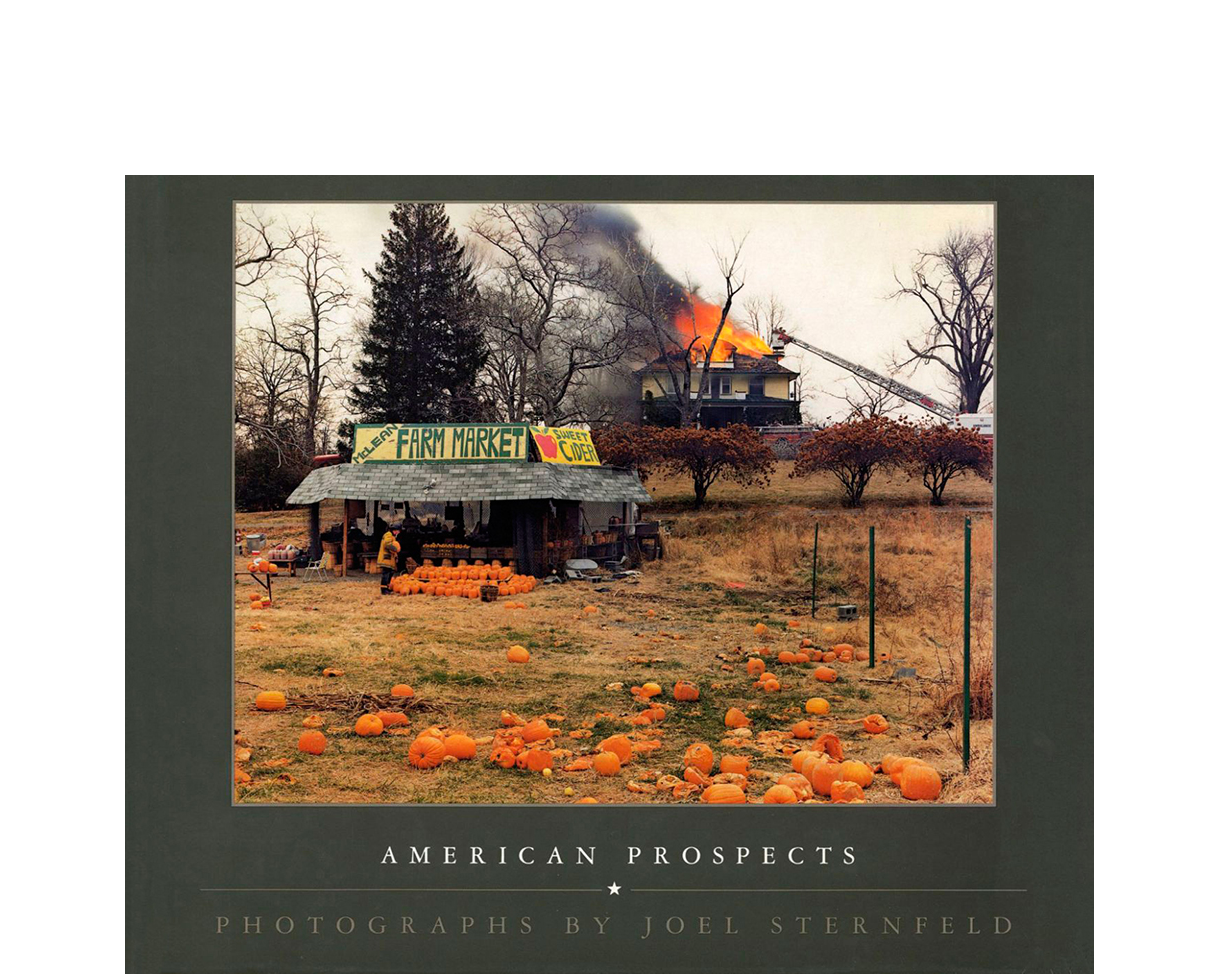

In Joel Sternfeld's provocative and frequently marvelous color photographs at Daniel Wolf Gallery (30 West 57th Street through Saturday), things seem to have gone awry in the relations between man and the rest of the natural world. In a picture called ''After a Flash Flood, Rancho Mirage, Ca.,'' an automobile lies belly-up in mud halfway down a freshly cut escarpment, while above it a nondescript bungalow teeters on the edge of destruction. In ''After a Tornado, Grand Island, Nebraska,'' a brick wall and an open refrigerator are all that remain of a house; next to them stands a tree devoid of limbs. Like insurance policies, these pictures suggest that the acts of God are not particularly friendly. ''McLean, Virginia,'' the most entertaining and unlikely picture of the exhibition, shows a fireman picking out a pumpkin at a farm market while behind him a house is in the process of being consumed by flames.

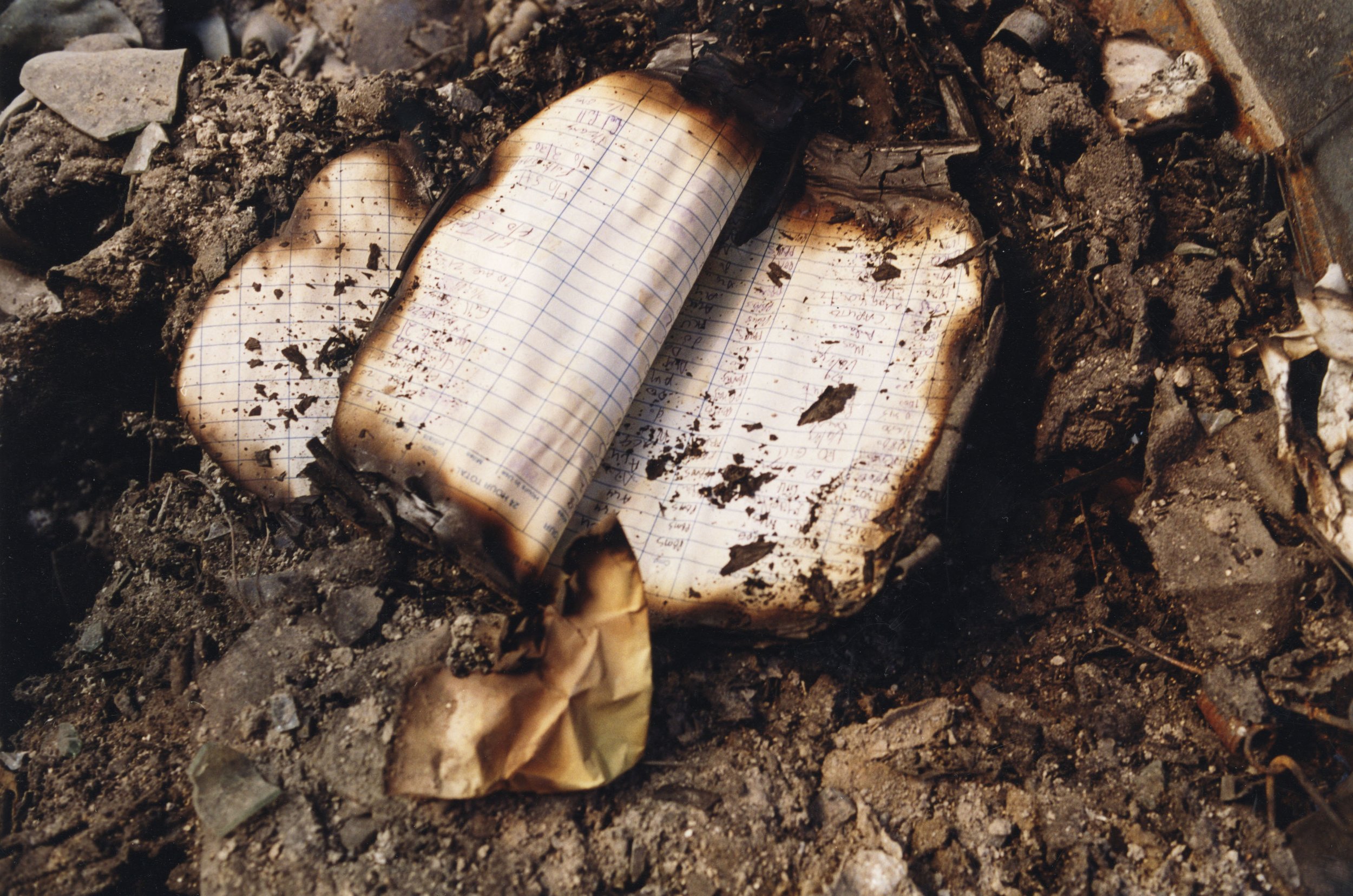

Elsewhere, ruin and decay prevail. New England mills and apartment houses have crumbled to heaps of brick; new construction scars our view of the Rocky Mountains. Man's presence on the land is made to seem peripheral, transitory, dysfunctional. Our dealings with our fellow animals are shown to be equally askew: an elephant lies collapsed on a country road, its neck roped to the truck that is leading it back to captivity and civilization; dead sperm whales litter an Oregon beach.

Given the myriad anxieties that haunt us today - nuclear proliferation and power plants, environmental pollution, acid rain - it is not surprising that catastrophe, disorder and discord should become topics in contemporary photography. What is confounding is that they should make an appearance in photographs that cause us to smile as frequently as they cause us to shudder. Partly this is because catastrophes et al. are only part of what Sternfeld envisions in his photographs of the American landscape, and partly it is because he is not another of photography's dour, holier-than-thou crusaders. Much of the time his eye is attracted to visual ironies of a less biting sort; sometimes it is waylaid by the gorgeous hues of a sunset.

A spectacular view of a valley near Ketchum, Idaho, is typical of the complexity Sternfeld is able to engage: in the foreground a man is sawing wood; next to him is a trailer that resembles a Quonset hut; beside the trailer are a 10-speed bicycle, two milk cans and a field full of sheep; beyond the sheep are three pseudo-rustic vacation homes in various stages of construction and, beyond them, majestic hillsides dotted with conifers. The juxtapositions defy brief enumeration - the man and the sheep, the trailer and the vacation homes, the 10-speed bike and the trailer, the vacation homes and the lush hills, one could go on and on - yet each defines an essential aspect of today's inhabited terrain. Man is compared to animal, true rustic to pseudo-rustic, trendy to nostalgic, hillside to habitation. In short, the photograph is responsible for the meanings that reside in its details. Moreover, Sternfeld's ability to organize all these layers of visual data into a formally coherent whole convincingly demonstrates his talents as a picture maker.

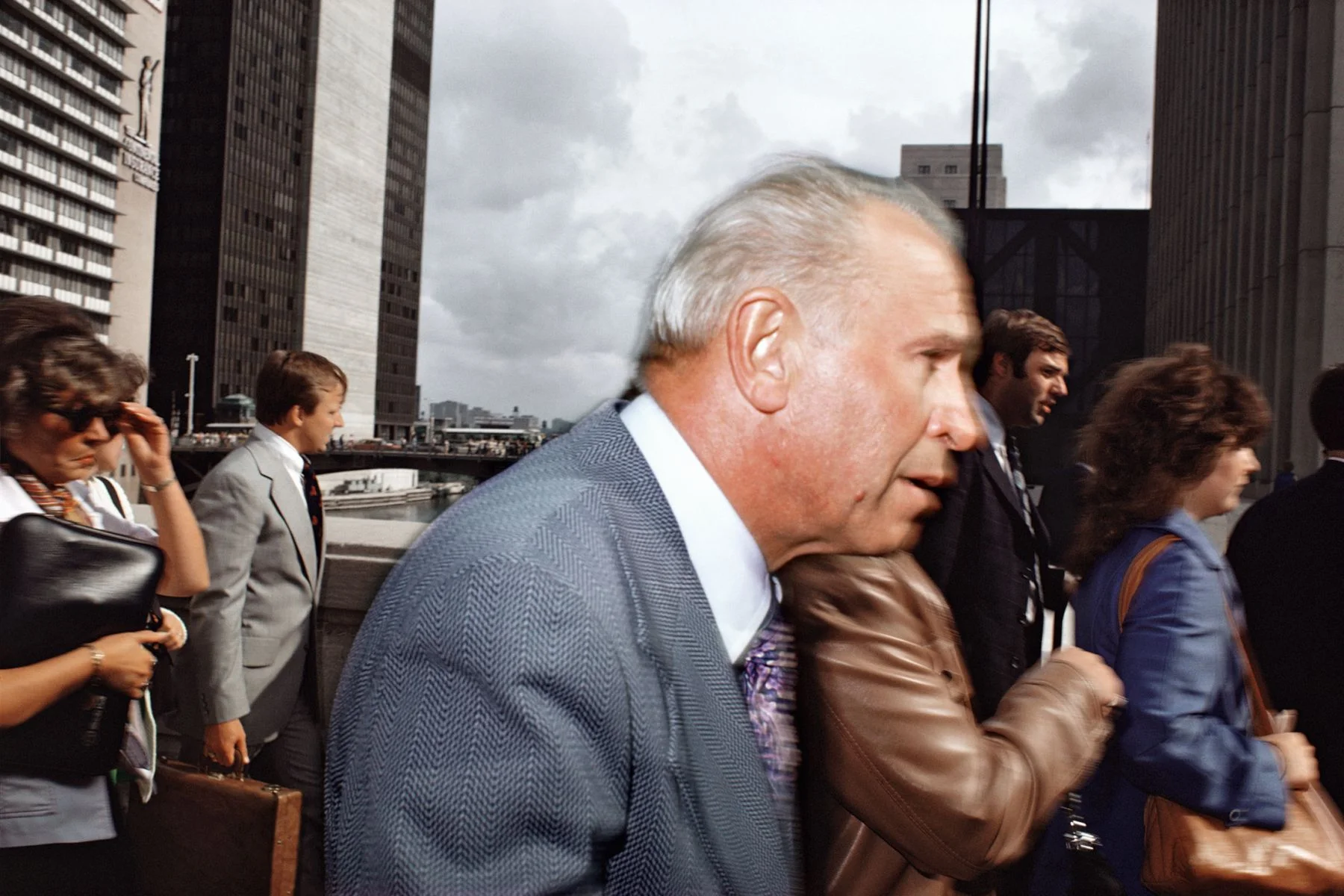

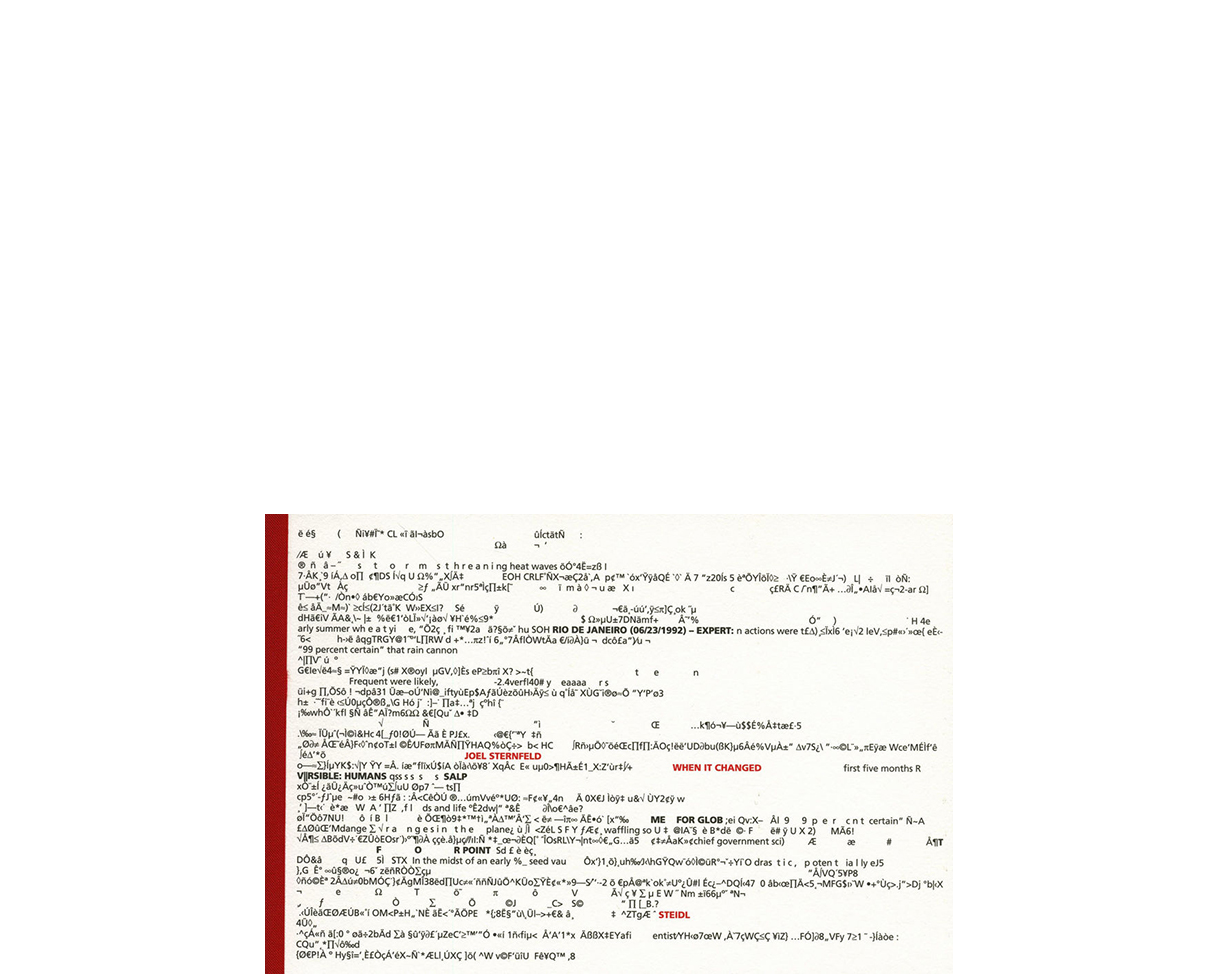

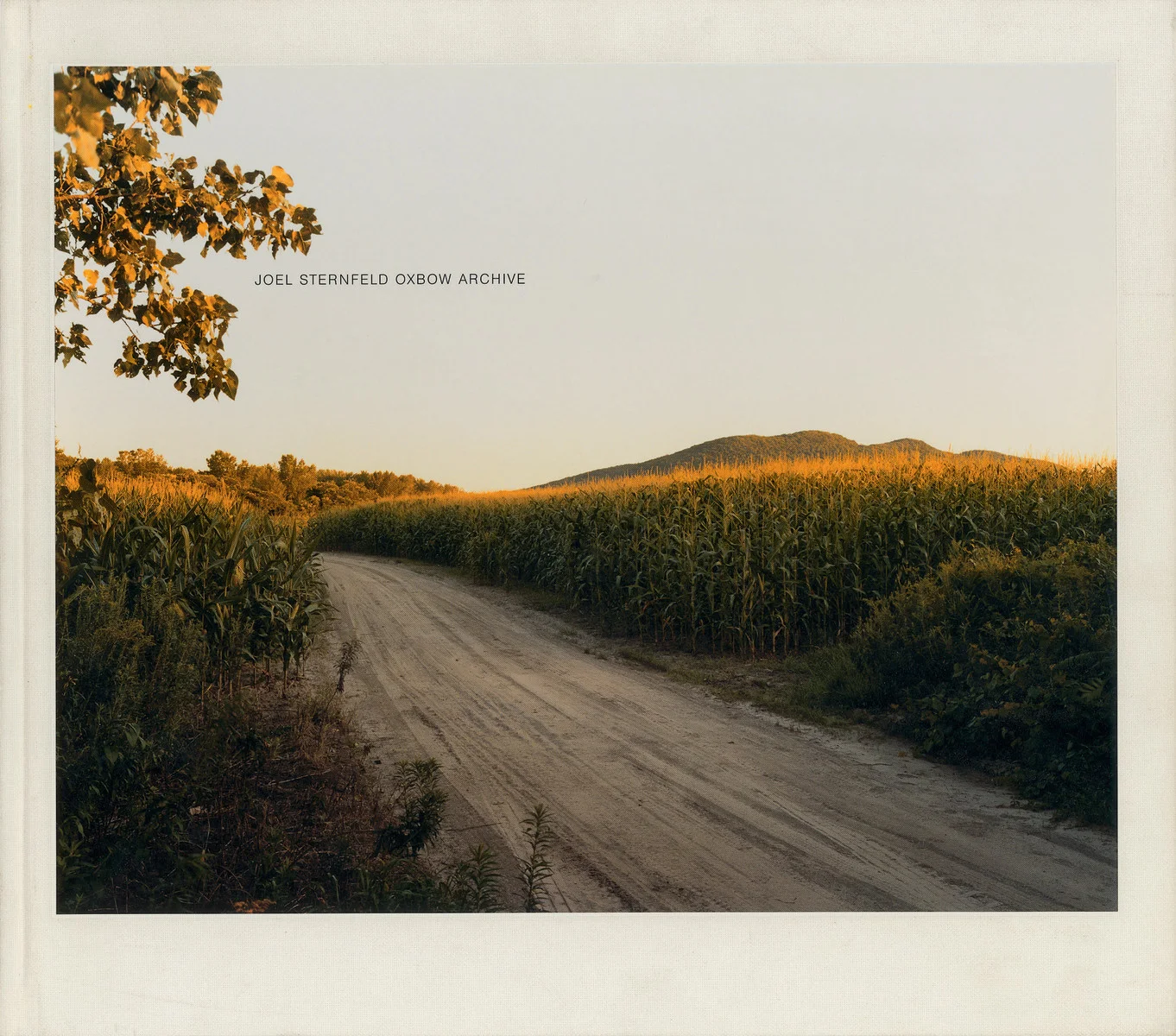

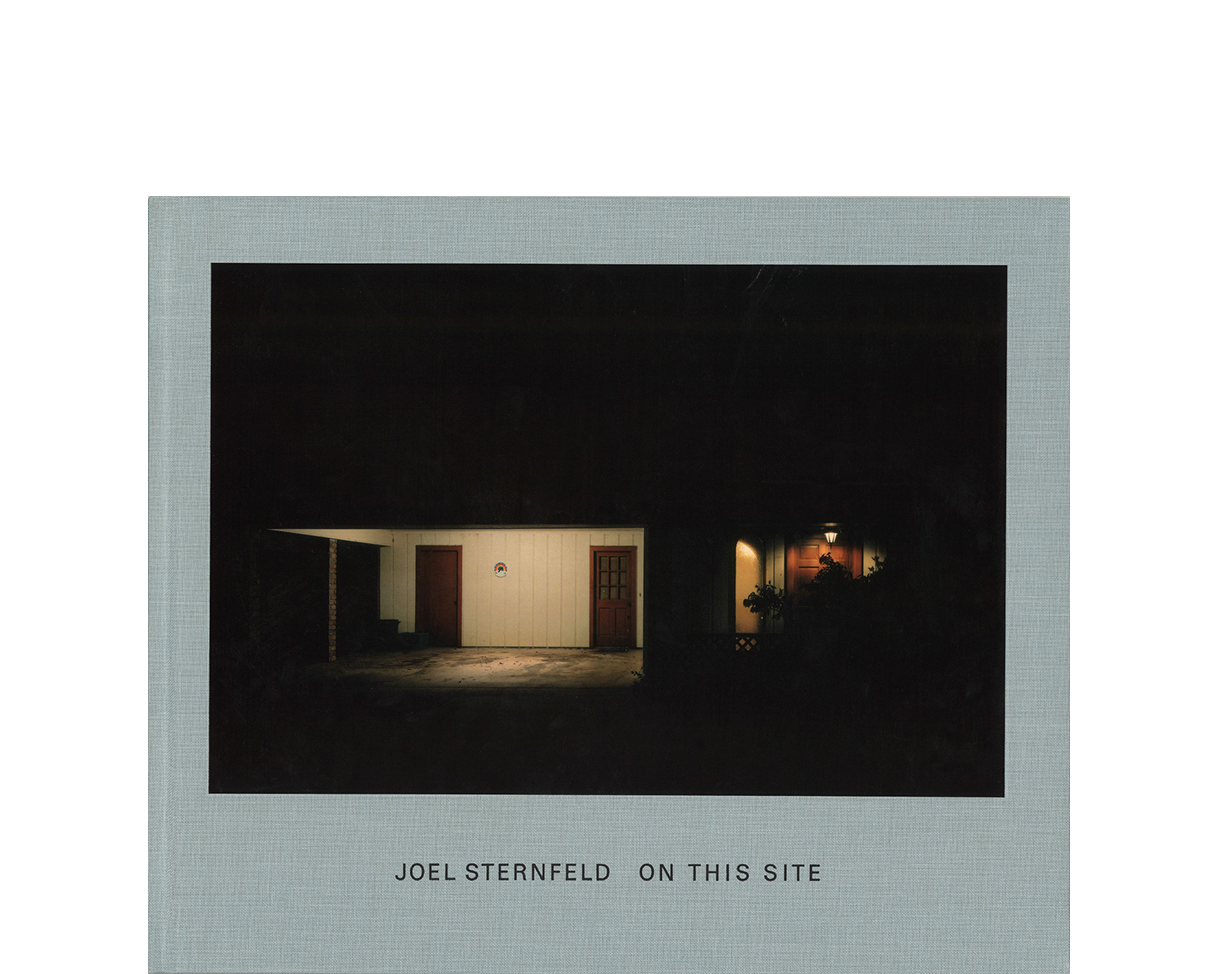

The 35 pictures in the exhibition were taken in the last three years, after Sternfeld acquired an 8x10 view camera and went ''on the road'' criss-crossing the country. (He had been doing color photography since the 70's began, but it was not until 1978 that his work came into its own. This is his first solo exhibition in New York.) Like Walker Evans and Robert Frank, earlier photographers who attempted to comprehend America in their work, Sternfeld found much to criticize in the culture; unlike them, he has been able to find signs of hope, if not redemption. His photographs tend to be less skeptical and more sentimental. His journey from innocence to experience seems to have tempered his indignation and made the pictures more resonant and dense. (The early photographs here - the farm market picture of 1978 or the exhausted elephant of 1979, for example - are shocking but not always complex; like one-line jokes, they may dull with familiarity.)

In addition to following in the tradition of chroniclers of the American experience, Sternfeld works within the traditions of American landscape photography. Were his pictures colorless, unmarked by man and confined to the West, one might mistake them for 19thcentury views. He is one of a number of photographers of his generation (he was born in 1944) to focus on the landscape as it has been altered by man; one thinks of the black-and-white photographs of Robert Adams, Frank Gohlke and Joe Deal, or, in color, of Stephen Shore and Joel Meyerowitz. But as much as he shares their concerns, Sternfeld makes quite different pictures. He is not as deliberate and circumspect as Adams, Gohlke and Deal, as emotionally remote and apparently bland as Shore, nor as carried away by the luminist potentials of his materials as Meyerowitz. Also, his pictures are notable for the variety of emotional responses they elicit; one can find them humorous, poignant, pretty, bizarre, even charming.

To evoke these responses, most rely on small incongruities - incongruities that the seductive beauty of the prints themselves tends to mask. Some careless viewers may walk away from his picture of beached whales thinking that they have just seen a beautiful Pacific seascape, I imagine, but most, attracted to the picture by its classic composition and color, will be taken aback by their ''discovery'' of the whales' carcasses. Scale is such an important device in Sternfeld's rhetoric that he makes it explicit in two pictures: one shows a child's sandbox-sized construction site in front of newly built houses, the other an apparently gargantuan woman leaning into a scale-model replica of Main Street, U.S.A. The incongruous details and the pictorial beauty of the photographs (enlarged from 8x10 negatives) for the most part are kept in precarious balance - a balance that defines the nature of Sternfeld's achievement. Without the incongruous, the photographs would be sentimentalized by their conventionally beautiful color; without their readily apparent beauty, they would lack the crucial sense of disjunction - the frisson that is at once a shiver of delight and a shudder of discomfort.

Moreover, the photographs build meaning by accretion, as if they were chapters in a novel. Some are hung to form obvious series - landscapes containing military ships, tanks, helicopters and rockets are grouped together, for example - but primarily the accretion involves the repetition of certain motifs. Dead trees, tract homes, fallen buildings, the detritus of junk-food, amusement-park culture - by the exhibition's end the photographer's concern for the land and dismay over man's depredations become quite clear.

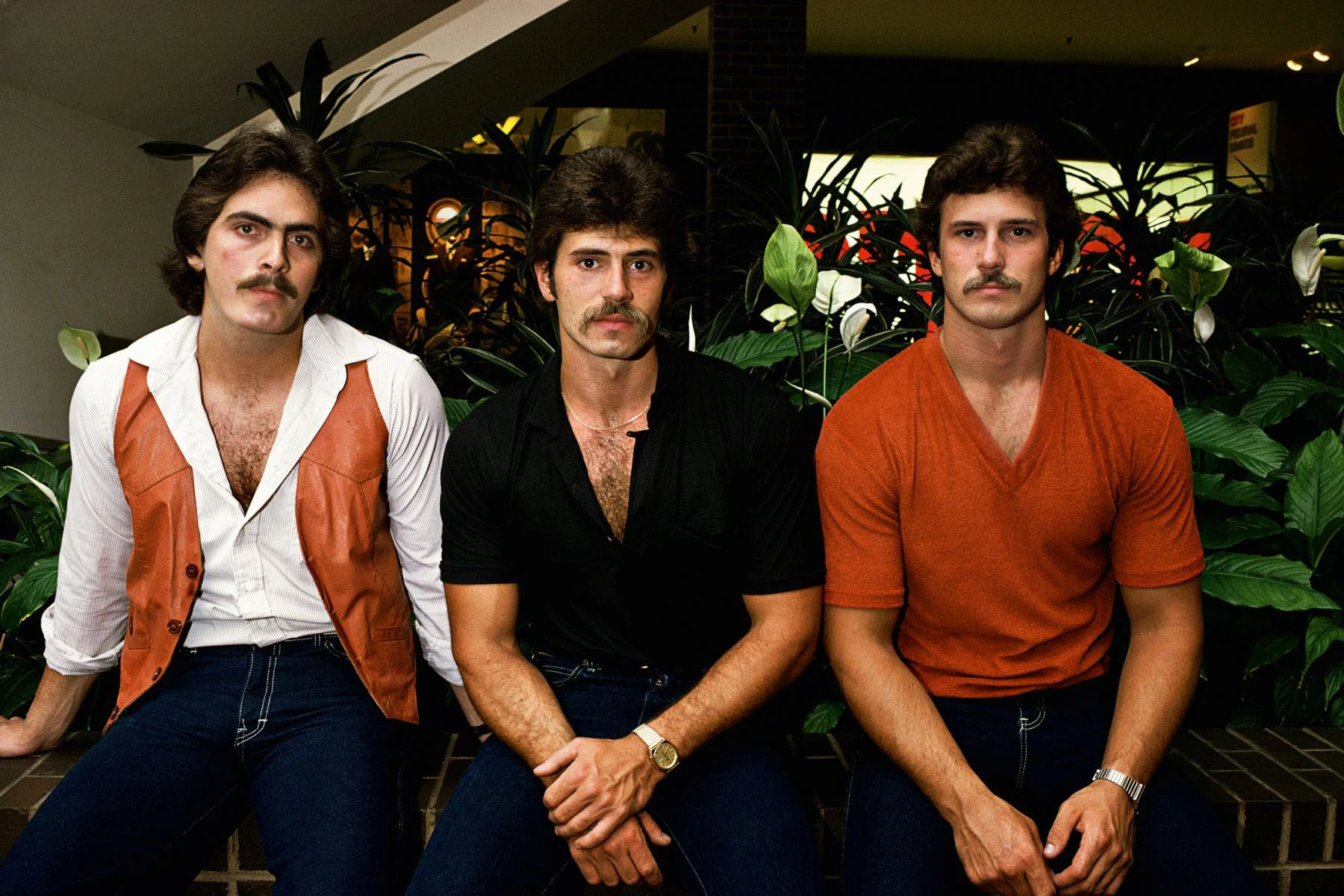

Another mark of distinction of these photographs is that they concentrate on the stratum of society one might call ordinary life. In doing so, they challenge Susan Sontag's assertion (in ''On Photography'') that ''traveling between degraded and glamorous realities is part of the very momentum of the photographic enterprise.'' Sternfeld has no romance going with the dispossessed, as Evans, Frank and so many other photographers have had (and continue to have), nor does he seek to reject his own middle-class roots for a more fashionable milieu. Instead of searching for the exotic, he finds the commonplace incredible. At his best he rerepresents the familiar, showing us a reflection of ourselves that is, like the one in a fun-house mirror, at once unfamiliar, amusing and disconcerting.

(Sternfeld's photographs also can be seen at the International Center of Photography, 1130 Fifth Avenue, in a group exhibition called ''The New Color,'' through Nov. 11.)

Word count: 1281

Copyright New York Times Company Oct 25, 1981