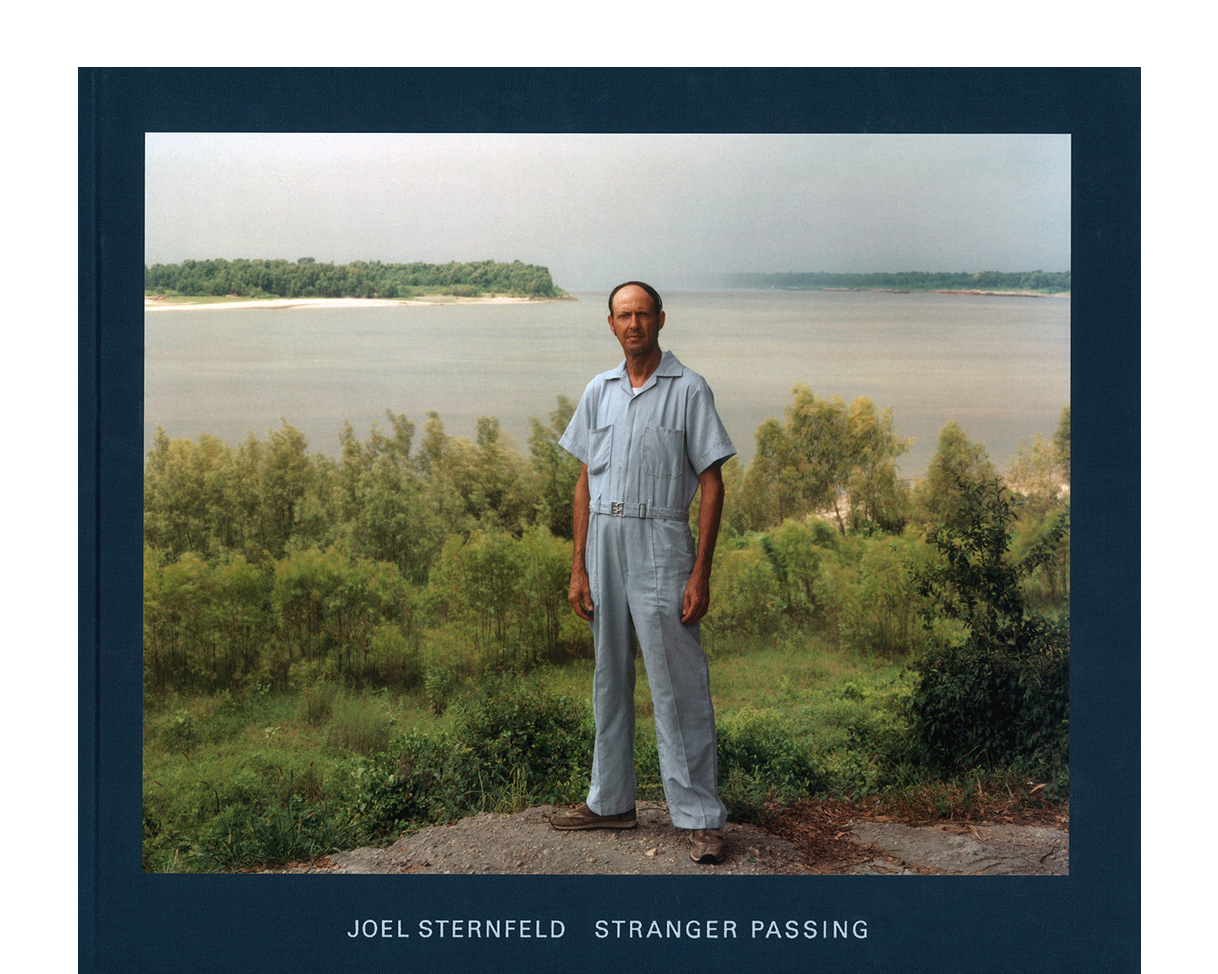

American Beauty in Atypical Places

We go forth all to seek America. And in the seeking we create her. In the quality of our search shall be the nature of the America that we create.

Waldo Frank, Our America

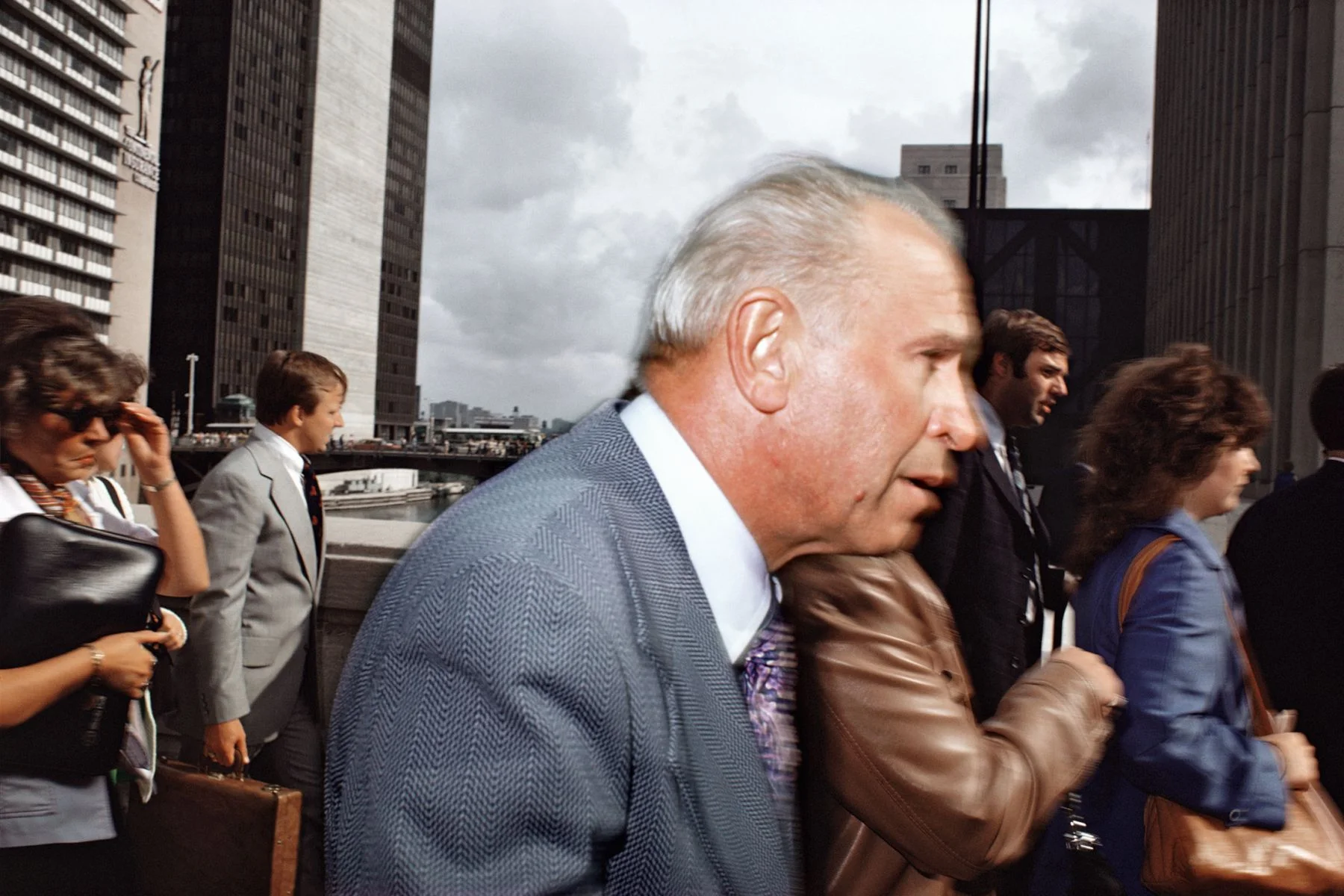

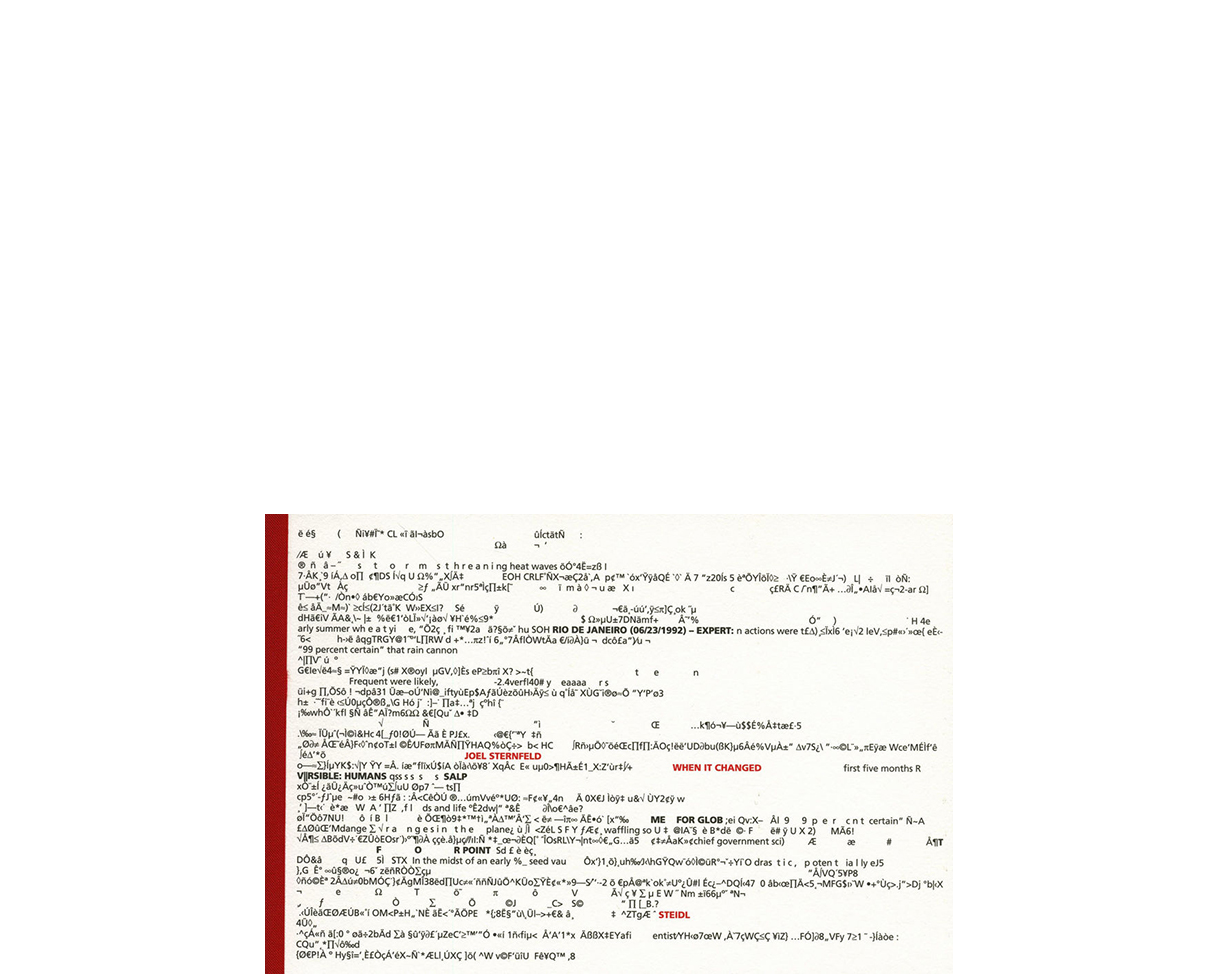

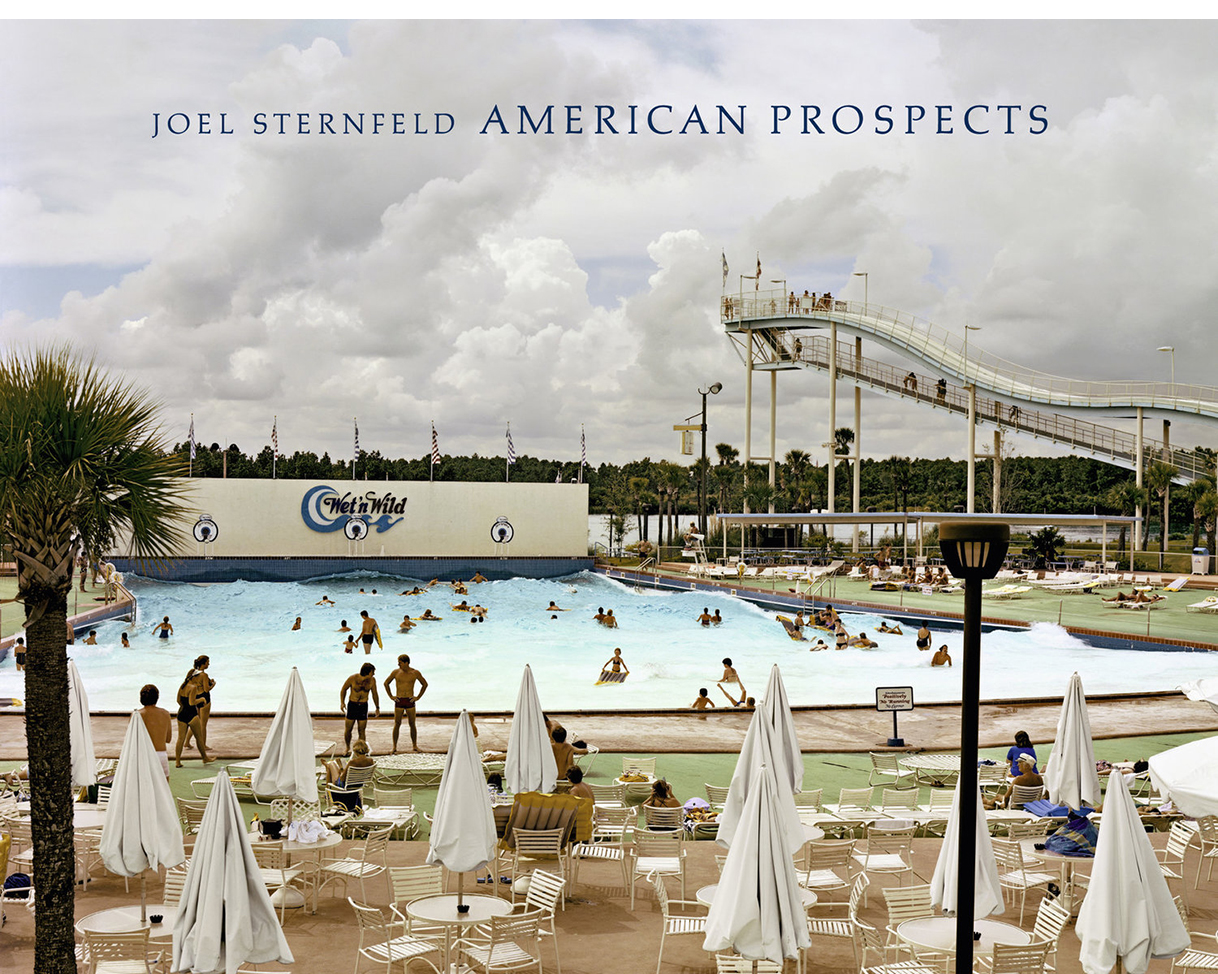

By the title American Prospects, Joel Sternfeld might be referring both to America's future and to its commanding views. Looking out might be both physical and mental, phenomenological and psychological. Eschewing both the heart of large cities and America's remaining wilderness, Sternfeld concentrates instead on the juncture of the two, where man has altered the land for purposes of domesticity, agriculture, industry, or pleasure. Sternfeld focuses on man as the earth's caretaker. In that role, modern man has been preserver, decorator, transient, controller, spoiler, and imitator-with both success and disaster.

Equally important, these are American landscapes. They are specifically of Troy, New York; Bear Lake, Utah; Beverly Hills, California; Houston, Texas; and Century Village, Florida. While many of the issues Sternfeld addresses are also relevant to other Western cultures, his titles remind viewers that these images are made in America and maybe perceived in the cultural and historical context of this nation. Sternfeld has studied the industries, seasons, geology, and vegetation natural to each region. He has read American literature attentively for details of regional life. His photographs record abandoned mills and river towns in New England, military bases and retirees in the South, ranchers and dude-ranch riders in the West, and colonial homes with dogwood trees in the Southeast.

Since 1978 he has periodically crisscrossed the country, usually traveling alone in a Volkswagen camper. Twice, he traveled and photographed for at least a full year; some trips lasted only a week. While carefully documenting regional characteristics, Sternfeld's pictures reveal that American life is being increasingly homogenized-for example, by the media, nationally distributed products and services, and the importation of whole environments. Never mind that Orlando, Florida, is landlocked; the Wet 'n Wild Amusement Park provides ocean-size waves. And green lawns decorate the arid Southwest, courtesy of water diverted from rivers hun dreds of miles away. Sternfeld also documents updated versions of traditional rituals: bikers traveling in convoys, like wagon trains; modern methods of collecting maple syrup; and a beauty contest held around the pool of a singles bar in Ft. Lauderdale.

He has found beauty in atypical places. Rather than photograph extraordinary natural wonders such as the geysers, towering peaks, or vast salt lakes favored by other landscape photographers, Sternfeld photographs inhabited places. His roads, rails, and riverways lead through civilized land to known destinations, for he explores the ordinary aspects of life. His audiences are asked to pay attention to scenes and details habitually unnoticed.

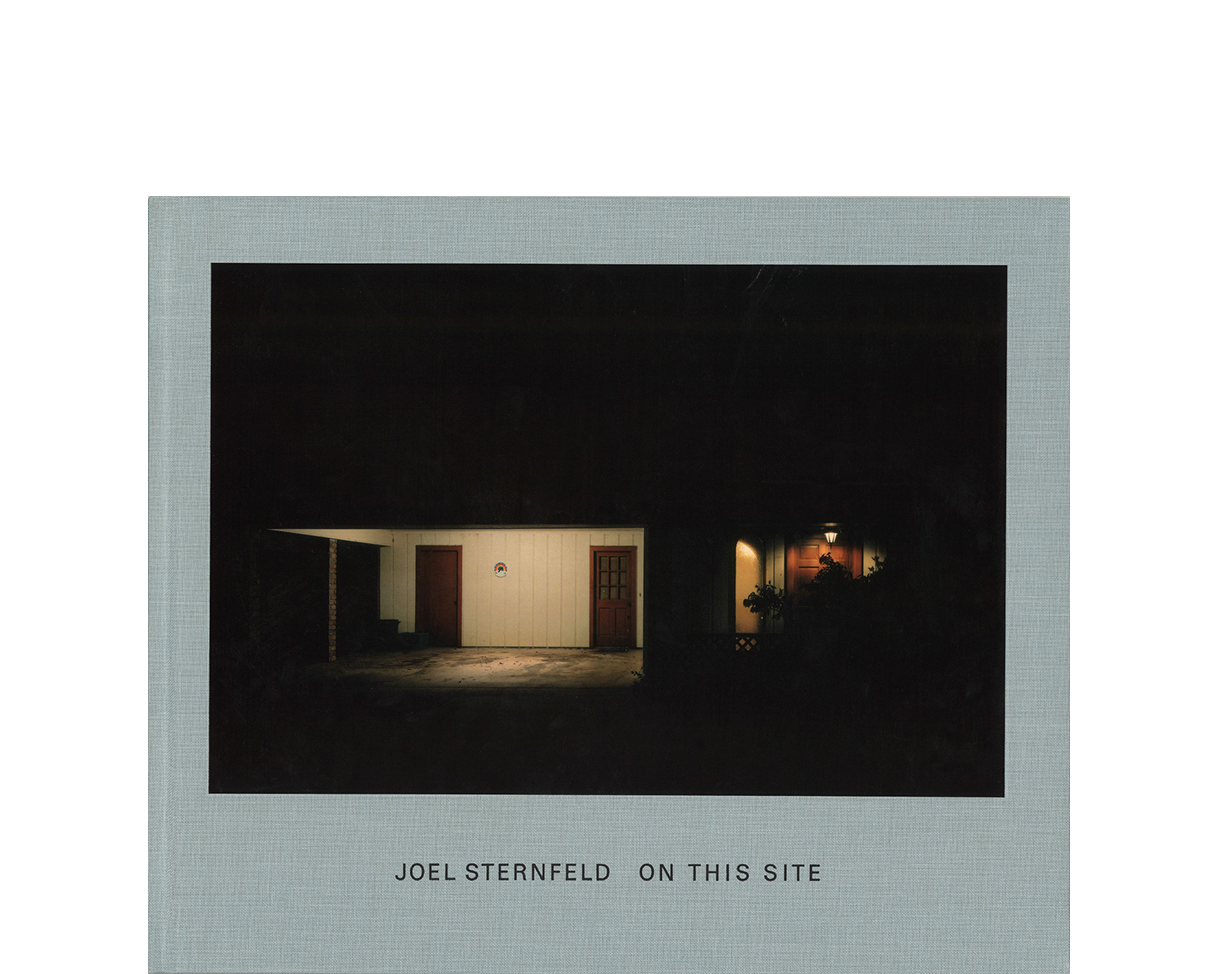

While plying the main routes, Sternfeld avoids taking pictures of such pictorial cliches as gas stations, storefronts, eateries, and motels. Neon screams and strident Day-Glo graffiti are also omitted. Perhaps he is conscious that this visual territory was richly described by such predecessors as Walker Evans and Lee Friedlander.

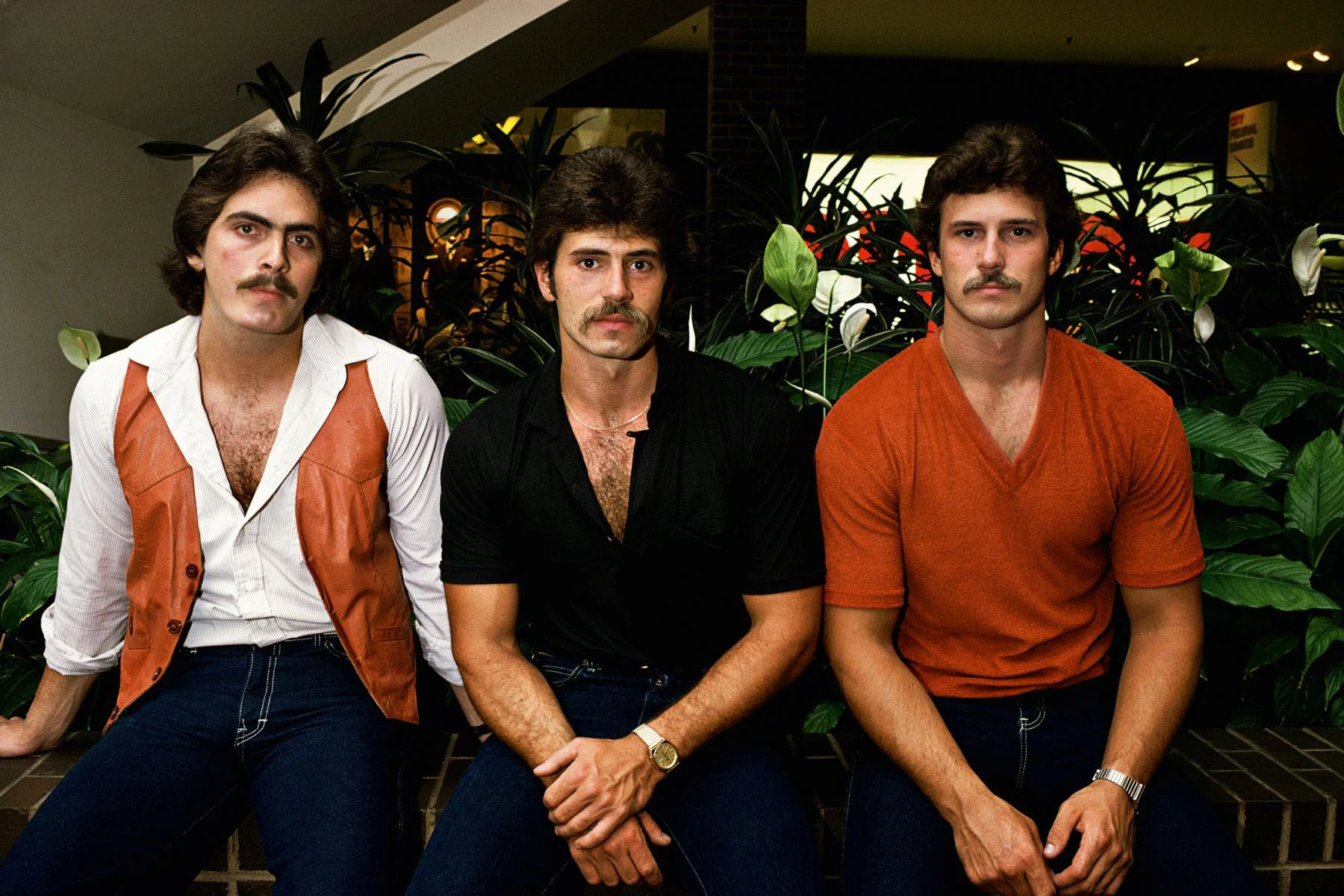

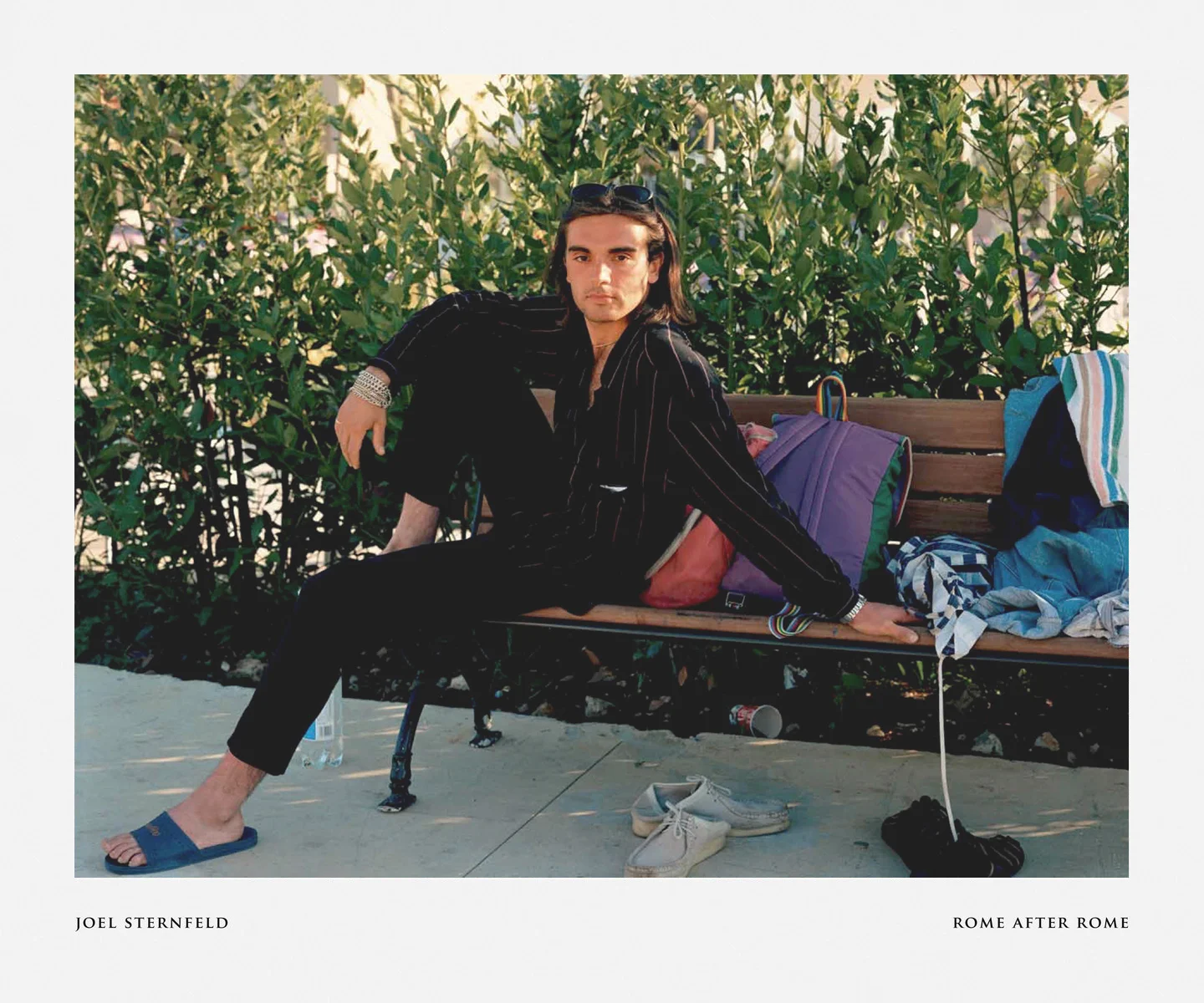

Many of his photographs are taken in the suburbs. He returns to them again and again, acknowledging the human needs and social expectations expressed through homes. In 1982, Sternfeld began to photograph the inhabitants of his landscapes. The portraits began with dispossessed, unemployed families living in a tent city outside of Houston (plate 37). Two hundred and fifty people lived in tents in a roadside park. The situation was symptomatic of the times; eleven million Americans were unemployed in that winter. However, most of his portraits are not of victims of the economy, but are of subjects from the American middle class. His sitters include California punks (plate 44); a blond father and a daughter in Canyon Country, California (plate 6); girls and their grandmothers in New Hampshire (plate 54); and a pink-shirted lady from a Page, Arizona, trailer park (plate 11). These too are America's prospects.

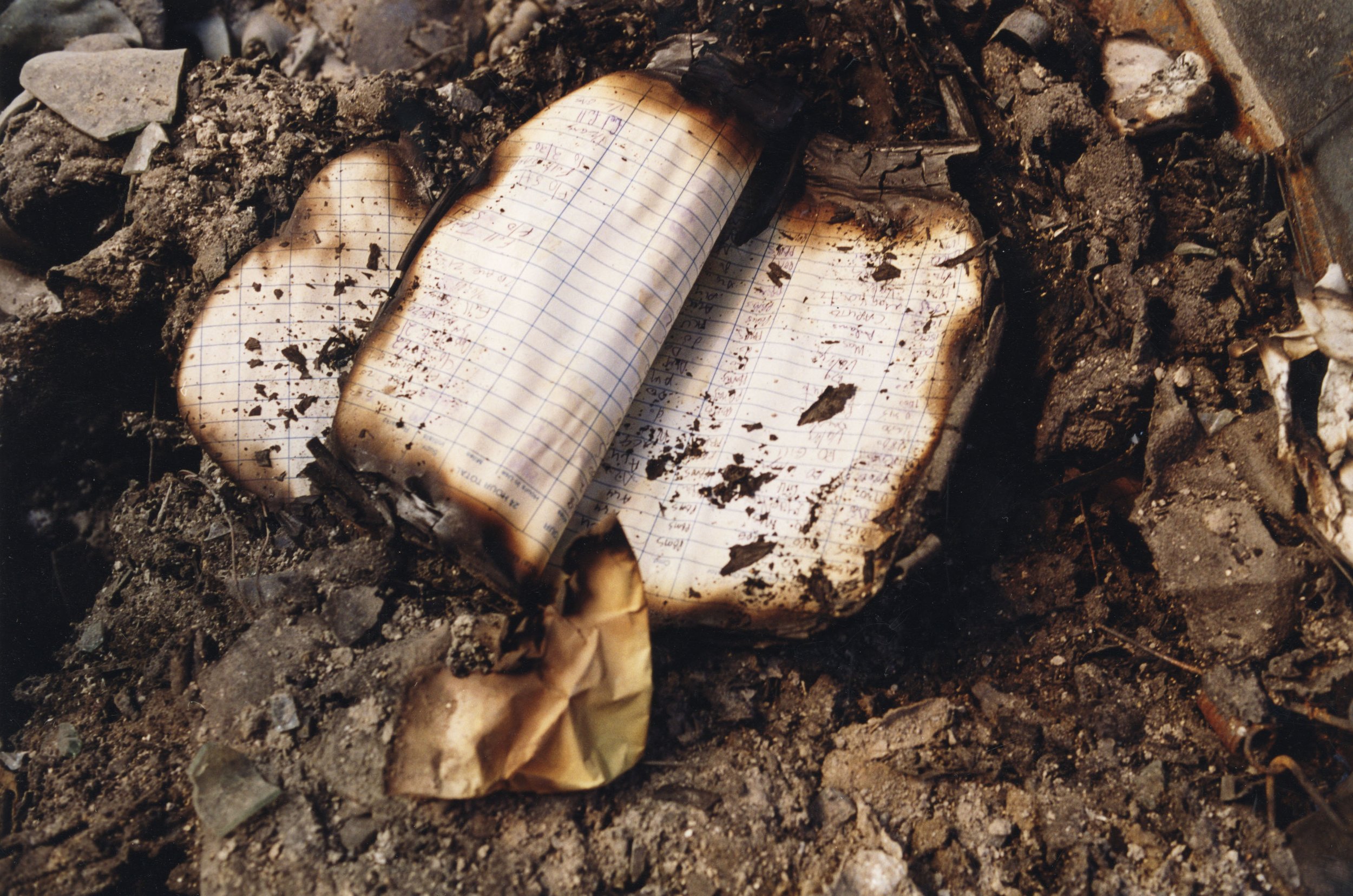

Workplaces also appear in these pictures, ranging from small factories in the Northeast to the shiny world headquarters of Manville Corporation in Littleton, Colorado. In his pictures of the Northeast, Sternfeld typically includes the nearby river or railway essential to early industrial development. Railroads made it possible for industry to leave the river; interstate highways allowed them to move anywhere.

How viewers react to pictures of factories may vary. In looking at the abandoned building in Grafton, West Virginia (plate 33), someone from that region might respond with nostalgia, an environmentalist with horror, an unemployed worker with anger, and a formalist artist with pleasure. To this writer, the Grafton factory building seems incongruous with the scale of the landscape. In building giant structures, man has rescaled the American landscape in the last hundred years. Sternfeld's pictures of industry evoke many of the above responses. His pictures reveal pleasure in the formal beauty of old buildings. But the somber skies and dark light speak of declining towns, abandoned dreams, and past prosperity.

Knowing the specific histories of these factory sites makes Sternfeld's objectives more understandable. For example, Manville Corporation of Colorado is the new face of the "bankrupt" asbestos manufacturer, the Johns-Manville Corporation of New York. Shiny and new, the corporate headquarters is crouched behind a protective boulder thousands of miles from the corporation's widely publicized troubles. The relocation puts a new twist on popular assumptions about the revitalizing power of nature.

Looking at these pictures of industry and then turning to the suburban photographs or the American portraits, one realizes that the subjects are not entirely new. We have seen most of these elements before, but not combined in quite this way. Their juxtaposition is the source of freshness in Sternfeld's vision. His primary tools are distance, color, disjunction, and humor.

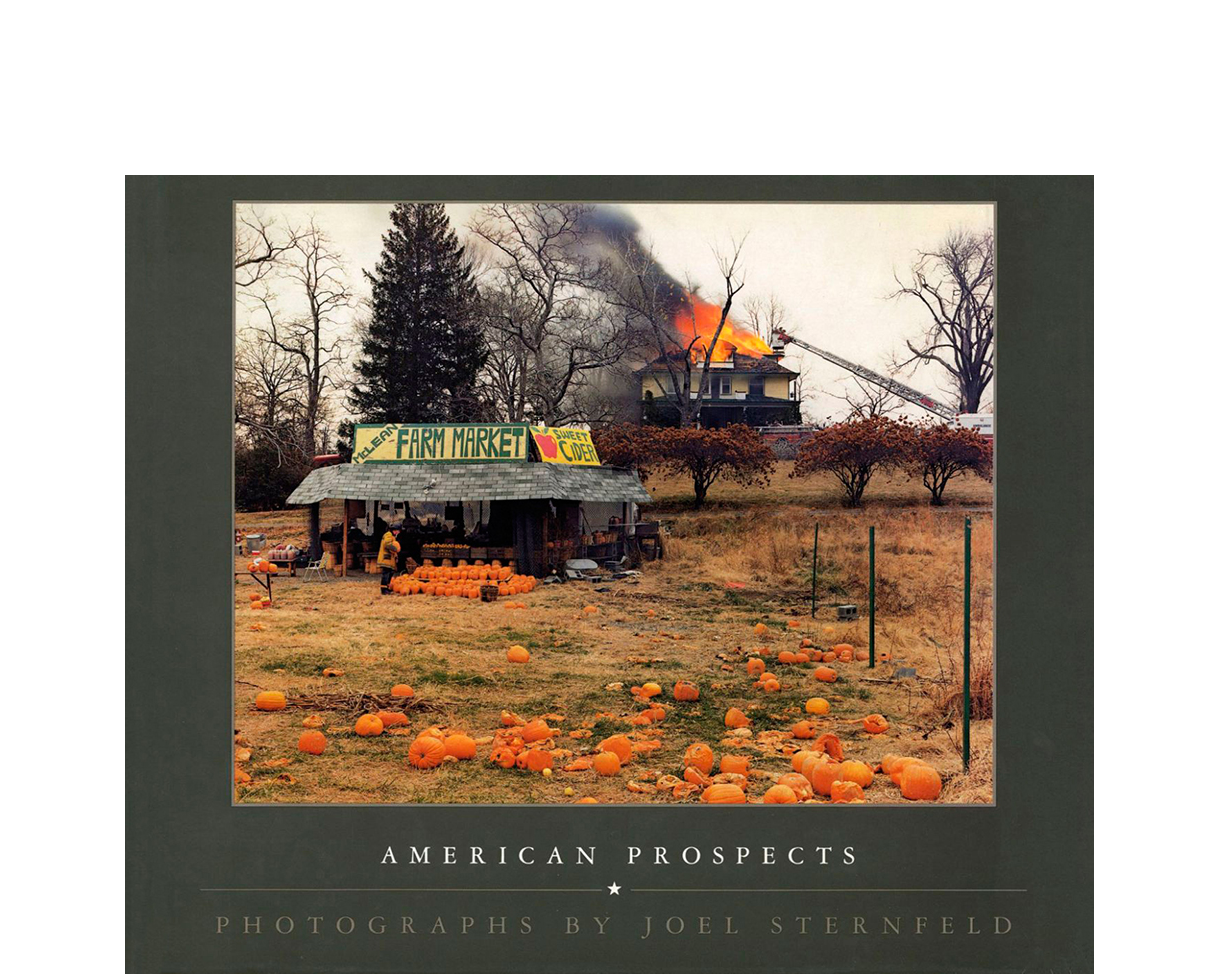

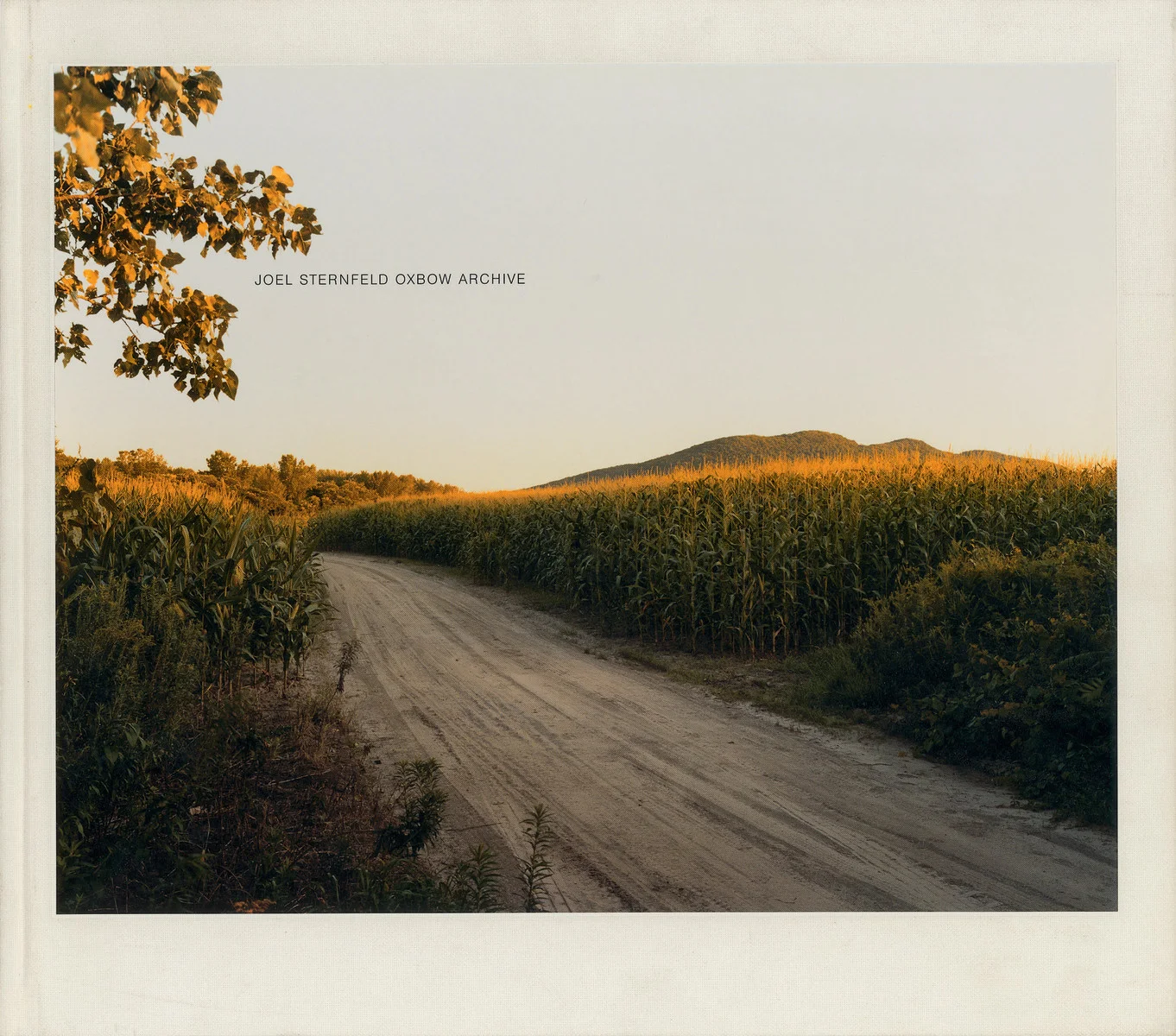

Sternfeld sometimes covers minor news events: a house fire, beached whales, the Texas stopover for the space shuttle. But by maintaining his distance, he keeps the event in a broad context. Newspaper journalists focus on events, especially disasters, at close range, both to provide information and to offer vicarious involvement. With Sternfeld, his position in relation to what is photographed is pivotal. He frequently positions himself high and distant, so that the picture's fore ground starts forty to sixty feet out from the camera. The photographer, and therefore his audience, is an observer, not a participant. This cools the picture's emotional tone by making it less seductively dramatic. The distance also allows Sternfeld to put more information in the picture, which is therefore more complex. What is one detail in his photographs might be the entirety of someone else's news photograph of the same subject.

Another distinctive aspect of composition in Sternfeld's work is that pivotal details are not centered in the frame. One almost always notices the sweep of the horizon first, and then something or someone in the lower half of the frame. He has the ability to skewer the chaos of incidentals against a timeless horizon. The effect is to engage the viewer with one element of the picture (e.g., the color or the sweeping vista) and to secure a final impression with the discovery of a very different element.

Color adds another level of complexity to photography. Colors have their own formal and expressive lives apart from the context of the picture. For instance, something red or pink can be more festive than the object it decorates and also more festive than the overall mood of the picture. An intelligent photographer can use these independent qualities of hues to unleash color from the confines of its context. The choice of photographic materials, time of day, and quality of light in which a photograph is made, plus the photographer's darkroom skills, permit great latitude of invention.

Sternfeld keeps bright colors in check and instead works in somber or pastel ranges. He makes a striking use of brown in After a Flash Flood (plate 5), where one doesn't at first see the car that has catapulted into the ravine because one's eye is initially drawn to the lighter-toned houses and mountains. Only as one looks at the picture more carefully is the scene revealed as one of destruction. Similarly, the renegade elephant in Woodland, Washington (plate 49), is another instance where the viewer's impression is initially directed away from significant features. A gray elephant on a dark gray road lets the viewer's eyes scan much of the picture before seeing the most important thing. Many photographers would have either gotten closer or shifted their vantage point to heighten awareness of the prostrate elephant. Sternfeld seems to recognize that the process of discovery is part of the pleasure of a picture.

Further examples of using opposing color dominance and significant object focus to create complex, seductive pictures include Near Vail, Colorado (plate 29), and Coeburn, Virginia (plate 24). In the former, brilliant yellow aspen trees catch the eye before one sees the rusting automobile carcasses below the trees. In the latter, two long, open-car coal trains snake past hillsides of blooming redbud trees. The contrast between the colorful hills and the dingy slashes of coal is striking. This incongruity keeps the pictures fresh.

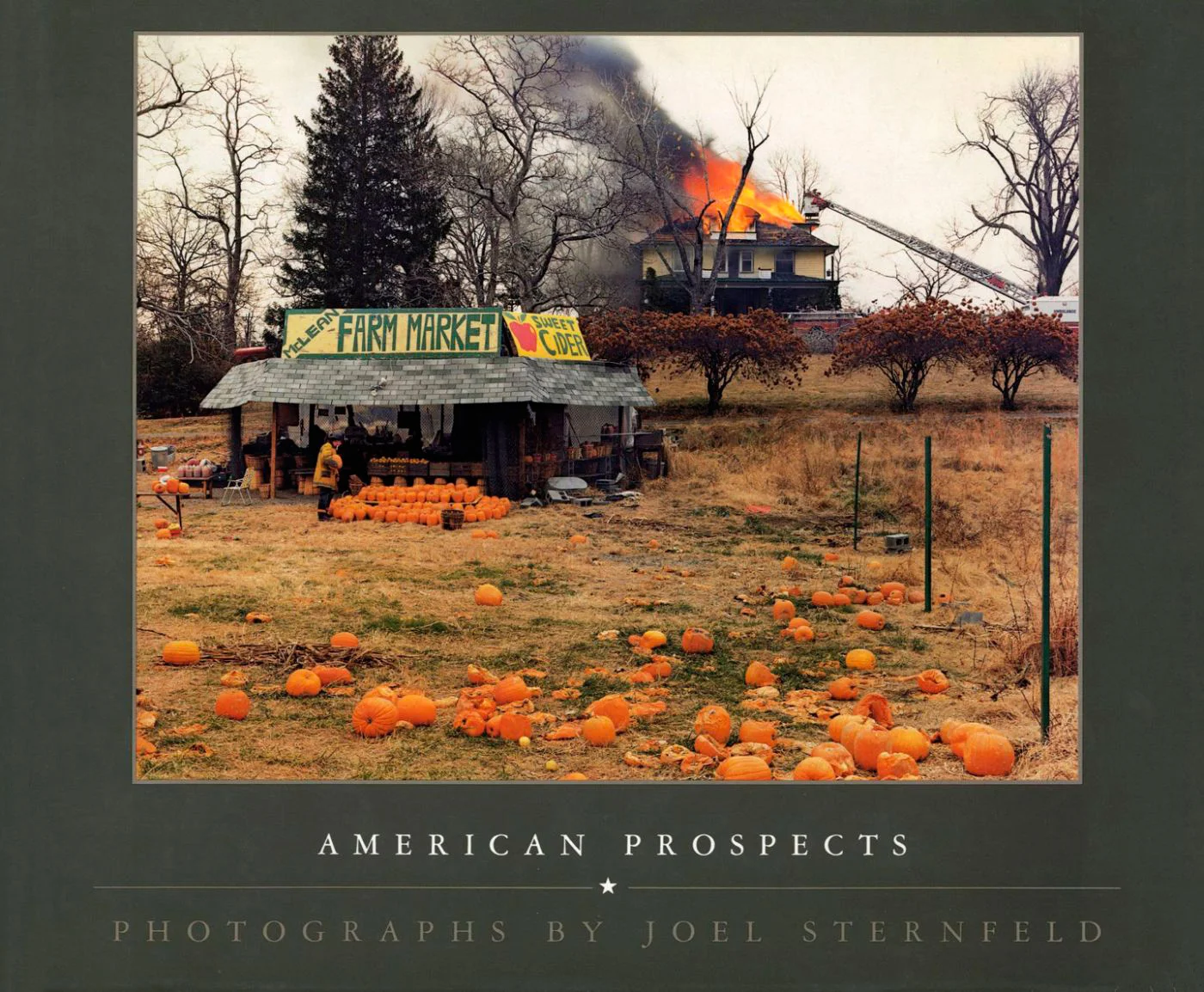

The seriousness of these pictures is relieved by humor. Sternfeld is a choreographer of ironic detail and the witty aside, laughing at man's humanity. His most popular photograph is Mclean, Virginia (plate 30), which shows a fireman shopping for pumpkins while a farmhouse burns on the hill above him. Flames rising from the roof dwarf other firemen precariously suspended in a mechanical bucket above the fire; one pumpkin in the crook of his arm, this modern day Nero considers additional purchases.

In Little Talbot Beach (plate 43), battleships sitting off the coast are like pink flamingos in someone's yard, a grotesque juxtaposition unintended by those responsible for it. Adding to the incongruity, a woman sunbathes on a lawn chair in the foreground. This emaciated woman is a comic pinup. She alludes to sexuality less substantially than the ships allude to violence.

Sternfeld successfully reuses this juxtaposition of a human figure and a military transport in several other photographs. In The Space Shuttle Columbia Lands at Kelly Lackland Air Force Base (frontispiece), a potbellied man in a T-shirt surveys the crowd that gathered to see the Columbia on its maiden voyage from California to Cape Kennedy. Because he is closer to the camera, he appears to be equal in size to the shuttle. His relaxed posture makes striking contrast to the shuttle's sleek design. In 1979 this photograph captured the public inspection of a soon-to-be-realized American dream, with a humorous aside added by the man in the fore ground. The meaning of this picture has changed since the tragic explosion of the Challenger in January 1986. Now the shuttle program signifies American technology gone terribly wrong.

In photographing ordinary life, Sternfeld is part of a movement in American photography that began in the mid-seventies and looked back to the cool, almost clinical documents of the 1930s made by Walker Evans. The movement is referred to as the New Topographies, after the exhibition in which the photographers were first grouped together and in which their aesthetic position was defined. These photographers (including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Joseph Deal, and Henry Wessel, Jr.) do not see the world as hierarchical, and they work in ways that treat all components of an image equally, stressing no particular area of the picture at the expense of another. They aspire to a level of objectivity and neutrality that has led critics to speak of these photographers as being invisible in their work.

Like New Topographic photographers, Sternfeld is objective, but he is not as detached. Through significant detail and dramatic spectacle, he seems more will ing than some of his contemporaries to entice particular responses from the viewer. He photographs the ordinary but with a twist: a suburb with storm clouds, a beach with a battleship, a desert with a basketball hoop. Like many of the New Topographic photographers, he works with an 8 x 10-inch view camera that allows him to precisely record infinite detail, but unlike Adams and others, he works in color. He maintains a precarious balance between beautiful colors and loaded details that keeps the mundane quality of the subject matter in most of the pictures from prevailing.

The large-format view camera is a highly unusual piece of equipment with which to photograph news events or to portray people in their natural habitat. The measurements-eight by ten inches-describe the size of the photographic negative. A large, bulky camera, it is generally used only for photographing inanimate objects and landscapes. Most photographers who take pictures of people outside studio settings prefer much smaller cameras because of their greater portability, and they willingly sacrifice the greater technical range of the view cameras.

Other contemporary photographers would rather mold new objects and create new environments to photograph than find existing subjects. Sternfeld's work is both of the world and to a purpose. It is perceptual, not conceptual. It is essential to Sternfeld's art that he has not manipulated his subject beyond asking the per son to pose. Given the implausible nature of some of the resulting scenes, the viewer must accept the veracity of the photograph.

As implied above, Sternfeld's pictures are not morally neutral. These beautiful color landscape photographs are seductive and pleasing to the eye, but on closer appraisal, one perceives that there is trouble in paradise. Conventional wisdom has it that technology is a negative force and that man can find salvation in nature. Sternfeld's photographs remind us that the issue is not always man's destructive effects on nature. Nature itself can be a source of oblivion. Rivers can flood their banks; earthquakes can rend the land. In these photographs, industry (technology) is threatening primarily when in the hands of the military. Perhaps technology, if not applied to objects conducive to oblivion, could help nature and man to be less cruel and deadly adversaries. What we lack is appreciation. Sternfeld's photo graphs make us more attentive to our landscape and our culture, that we might act more judiciously and competently with nature, each other, and ourselves.

Anne W. Tucker

This essay is indebted to :

Estelle Jussim and Elizabeth Linquist-Cock, landscape as Photograph, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1985; John Szarkowski, American Landscapes, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1981;

John R. Stilgoe, Common Landscapes of America, 1580-1845, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1982;

and various articles by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Nathan Lyons, Weston Neaf, and Beaumont Newhall.